Homer: The Iliad

Book XVI

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XVI:1-100 Patroclus asks to fight in Achilles’ armour

- Bk XVI:101-154 Patroclus arms as the ships burn

- Bk XVI:155-209 Achilles sends out the Myrmidons

- Bk XVI:210-256 Achilles prays to Zeus

- Bk XVI:257-350 Patroclus takes the field

- Bk XVI:351-425 Patroclus routs the Trojans

- Bk XVI:426-507 The death of Sarpedon

- Bk XVI:508-568 Glaucus rouses the Lycians and Trojans

- Bk XVI:569-683 The fight over Sarpedon’s body

- Bk XVI:684-725 Apollo directs the fight before the city

- Bk XVI:726-776 The fight over Cebriones’ body

- Bk XVI:777-867 The death of Patroclus

BkXVI:1-100 Patroclus asks to fight in Achilles’ armour

As they fought on around the benched ship, Patroclus, hot tears pouring down his face like a stream of dark water flowing in dusky streaks down the face of a sheer cliff, returned to Achilles, leader of men. Noble Achilles, the fleet of foot, saw and pitied him, and spoke to him with winged words: ‘Why are you crying like a little girl, Patroclus, like a child running by her mother’s side, begging to be carried, clutching at her skirt to make her stop, and tearfully looking up until her mother takes her in her arms? Your teardrops fall like hers, Patroclus. Have you bad news for the Myrmidons or myself, some tidings from Phthia known to you alone? Menoetius, Actor’s son and Peleus son of Aeacus, our fathers, are both still alive, men say, Peleus among his Myrmidons. Their death indeed would grieve us deeply. Or do you weep for the Argives, dying by the hollow ships, because of their presumption? Say, now! Don’t keep it to yourself: let us both know.’

Then Patroclus, great horseman, you groaned heavily in reply: ‘Achilles, son of Peleus, mightiest of the Greeks, restrain your indignation now great sorrow is come upon them. All our best men lie by the ships wounded by arrow or spear thrust: Diomedes, Tydeus’ great son, Odysseus, the famous spearman, Agamemnon too, and Eurypylus with an arrow in the thigh. The healers, skilled in the use of herbs, are busy trying to cure their wounds, while you, Achilles, remain intractable. May such anger never possess me as grips you, you whose useless valour only does harm to all. How will posterity benefit, if you fail to save the Argives from ruin? Pitiless man, you are no son it seems of Thetis or the horseman Peleus, rather the grey sea and the stony cliffs bore you, with heart of granite. If in your mind perhaps some prophecy deters you, some word of Zeus your divine mother relayed, then at least let me take the field now, leading the ranks of Myrmidons, so I may be a saving light to the Danaans. And let me borrow that armour of yours, so the Trojans might take me for you and thus break off the battle. Then the warrior sons of Achaea, in their exhaustion, may win a breathing space: there are few such chances in war. We who are fresh might easily drive a weary enemy back to their city from the ships and huts.’

So Patroclus made his request, fool that he was, for his own doom and an evil death were the certain answer to his prayer. Fleet-footed Achilles, answered passionately: ‘Ah, Zeus-born Patroclus, what words are these! I know nothing of any prophecy, nor has my divine mother relayed any word from Zeus, my heart is simply gripped with deadly grief, because a man has chosen to rob his equal, and snatch his prize, given the power. A deadly grief: and my heart has suffered deeply. The girl the Achaeans chose for me as prize, the girl I won with my spear when I took her walled city, Lord Agamemnon snatches from my arms, as though I were some exile without rights. But let us call all that past and done. It seems my anger wasn’t fated to last forever. I said indeed it would end when the sound of battle echoed about my ships. So then, now that a dark cloud of Trojans hems in the ships so closely, and we Greeks, confined to a narrow space, have nothing left at our backs but the shore, clad your shoulders in my glorious armour, and lead my Myrmidons, who love a fight, to battle. It seems the whole of Troy attacks us fearlessly, now they can see no sign of my helm, its visor gleaming in their faces. They would soon fill the river-beds with their dead, and not be warring round our camp, if Agamemnon were but warm towards me. It is not some spear in Diomedes’ hands will save the Greeks from ruin, nor that hateful voice, I fail to hear, of Atreus’ son, shouting his head off. It is man-slaying Hector’s call that rings in my ears as he urges on his Trojans, their cries that fill the plain, and they who conquer the Greeks in battle. Yet you must take the fight to them, and save the fleet from ruin, Patroclus, for our means of escape is lost once they set fire to the ships. Listen while I give you my advice, and you can win glory for me, and recompense from these Danaans, the return of that lovely girl and fine gifts as well. When you have driven them from the ships, come back to me. Even if Hera’s lord, the Thunderer, grants you glory, don’t press on against the battle-loving Trojans on your own: that will only lessen my chance of honours. In the heat of victory, as you lay about the Trojans in this fight, don’t make for Ilium, lest a god from Olympus comes to join the fray, for Apollo, the Far-Striker, loves them greatly. Return to me, when you have lit your light of deliverance among the ships, leave the rest to drive the enemy over the plain. By Father Zeus, Athene and Apollo, I wish the Trojans death to a man and the Argives likewise, and that we two might survive the ruin, to pry loose Troy’s holy diadem.’

‘Achilles warns Patroclus’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

BkXVI:101-154 Patroclus arms as the ships burn

As they spoke, Ajax was forced to retreat in a shower of missiles. He was conquered by Zeus’ will, and the efforts of the brave Trojans. The gleaming helm on his head rang, as its flanges took the blows time after time, and his left shoulder ached from swinging his glittering shield, though even the hail of missiles failed to beat it down. He gasped for breath, and sweat streamed from his limbs, unable to pause for rest, as savage attack followed attack from every side.

Tell me now, Muses, you who live on Olympus, how the Achaean ships were first set on fire.

Hector charged at Ajax and struck with his long sword at the ash pole near the socket at the top, shearing the head away, and leaving Telamonian Ajax brandishing a useless pike, its bronze blade clanging to the ground far away. Ajax shuddered deep in his mighty heart at the gods’ actions, and knew that Zeus the Thunderer, on high, intent on Trojan victory, was bringing all their battle plans to naught. So he fell back out of range, then the Trojans threw blazing brands into the swift ship, and a stream of living flame instantly engulfed it.

Now, as fire took the ship’s stern at last, Achilles struck his thigh and turned to Patroclus: ‘Up, Zeus-born Patroclus, Master of the Horse, I see a glare of flame by the ships. They must not take them, and cut off our retreat! Arm fast as you can, and gather the men.’

At his words, Patroclus began to clad himself in gleaming bronze. First he clasped the shining greaves, with silver ankle-pieces, about his legs. Next he strapped Achilles’ ornate breastplate round his chest, richly worked and decorated with stars. Over his shoulder he hung the bronze sword with its silver studs, and then the great thick shield. On his strong head he set the fine horse-hair crested helm, its plume nodding menacingly. Lastly he grasped two stout spears that suited his grip, though not peerless Achilles’ own great, long, and heavy spear that alone among the Achaeans he could wield, that spear of ash from Pelion’s summit that Cheiron gave to the warrior’s dear father Peleus, for the killing of men.

Then Automedon, whom he honoured most after Achilles, breaker of battle lines, and trusted most to keep within call in the fight, was ordered to harness the horses quickly. Automedon led Achilles’ fleet-footed pair beneath the yoke, Xanthus and Balius, swift as the wind, whom Podarge the Harpy, grazing a meadow beside Ocean’s Stream, conceived with the West Wind. In a side-trace too he harnessed peerless Pedasus, whom Achilles drove off when he took Eëtion’s city. Pedasus though mortal still kept pace with those immortal.

BkXVI:155-209 Achilles sends out the Myrmidons

Meanwhile Achilles made his round of the huts and called all the Myrmidons to arms. They gathered like a pack of ravening wolves filled with indescribable fury, like mountain wolves that have brought down a stag with full antlers, and rend it with blood-stained jaws then go in a mass to drink, lapping the dark water with slender tongues, dripping blood and gore, the hearts in their chests beating strong and their bellies gorged. So the captains and generals of the Myrmidons surged around Patroclus, while Achilles stood among them, marshalling charioteers and infantry.

Fifty were the swift ships Zeus-beloved Achilles led to Troy, with fifty men, his comrades, to man the oars. And five leaders he charged with issuing orders, he being supreme commander. The first company Menesthius led, he of the gleaming breastplate, the son of the river-god Spercheus. Lovely Polydora, Peleus’ daughter, bore him, a mortal woman who lay with the ceaseless stream, but in name he was the son of Borus, Perieres’ son, who married her freely and gave a handsome dowry.

The second Company warlike Eudorus commanded. His mother too, Polymele, a fine dancer, daughter of Phylas, bore him out of wedlock. Great Hermes, the Slayer of Argus, fell for her when she caught his eye, among the choir of girls on the dancing floor of Artemis, goddess of golden arrows and the sounding hunt. Hermes the Helper took her swiftly to her chamber and lay with her secretly. She bore him this glorious son, Eudorus, finest of runners and fighters. But when Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth, brought him into the world, and at last he saw the light, Echecles, son of Actor, powerful and steadfast, paid a vast bride-price and led her home. There her old father Phylas cherished and nurtured the child tenderly, loving him dearly as if he were his son.

Warlike Peisander, son of Maemalus, led the third company, the best spearman next to Patroclus among the Myrmidons. The old charioteer Phoenix led the fourth, and Alcimedon the fifth, the peerless son of Laerces.

When Achilles had marshalled them, under their leaders, in their separate companies, he gave them this stern injunction: ‘Myrmidons let none forget the threats with which you menaced the Trojans, while in my wrath I kept you here by the ships. You all accused me, saying: “Harsh son of Peleus, your mother nursed you on bile, pitiless man, keeping your comrades idle here, against their will. Since your heart is filled by this wretched anger, let us take to the ships and sail home again.” That was how you reviled me in your gatherings. Well now the work of war is upon you, such as in past days at least you loved. So, let each man find his courage, and fight against these Trojans.’

BkXVI:210-256 Achilles prays to Zeus

His words roused their bravery and their strength, and they dressed ranks more closely as their prince addressed them. Like the close-set stones in the high wall of a house, fitted tightly to defend it from the wind’s power, so their helms and bossed shields were ranked, shield to shield, helm to helm, man by man, so tightly packed that as they moved their heads, the horsehair crests on their gleaming helmet ridges touched together. Then Patroclus and Automedon, like-minded warriors, posted themselves at the head of the Myrmidons, ready to do battle.

Now Achilles left them, and went to his hut. There he opened the lid of a fine ornate chest that silver-footed Thetis had placed aboard his ship, filled to the top with thick wool rugs, tunics, and cloaks to keep off the wind. He kept a beautifully fashioned cup inside it, from which no other man was allowed to drink, which he used for libations to Zeus alone. He took it from the chest, cleaned it with a sulphur mix, then washed it and his hands in clear water, and filled it with red wine. Standing in the middle of the courtyard, he poured the wine on the ground, gazed at the heavens, and prayed to Zeus the Thunderer who listened: ‘Pelasgian Lord Zeus, who live far off, ruler of wintry Dodona, surrounded there by your Elloi, priests and interpreters with unwashed feet, who sleep on the ground, you who have heard me before when I prayed, who have honoured me by striking hard at the Greek army, fulfil my prayer now. I will stay here by the beached ships, but I am sending my friend with a host of Myrmidons to war. Grant him glory, far-echoing Zeus, and fill his heart with courage, so that Hector may know my companion’s skill in war, that his invincibility does not depend on my presence in the field. And when he has rid the ships of the foe and their battle-cries, let him return to the ships resplendent in my armour, he and his men unscathed by the close combat.’

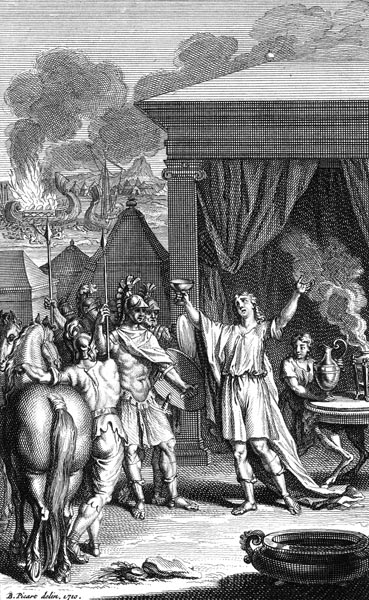

‘Achilles honours Zeus’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

So he prayed, and Zeus the Counsellor listened. One wish the Father granted, but the other he denied. Patroclus would indeed drive the enemy from the ships, ending their attack, but would not return safe from that battle.

When Achilles had finished the libation and his prayer to Father Zeus, he returned to his tent and shut away the cup in its chest, then took up a vantage point before his hut, keen to gaze on that fatal conflict between the Greeks and Trojans.

BkXVI:257-350 Patroclus takes the field

But the host of men ranked behind brave Patroclus marched out, full of confidence, to attack the Trojans, like a horde of wasps that foolish boys will stir to anger, poking the roadside nest, causing a public nuisance, since some passer-by may then rouse them unwittingly, and out they fly in a valiant swarm to defend their larvae. With the same courageous spirit the Myrmidons flowed from the ships, and with ceaseless cries. And Patroclus shouted loudly to them all: ‘Myrmidons, warriors of Achilles, be men, my friends, and fill your minds with furious courage, so we may win glory for the son of Peleus, greatest of the Argives beside the ships, and for his men who fight at close quarters, the pick of the army; and so the son of Atreus, imperial Agamemnon, may acknowledge his great blindness in failing to honour the best of all the Greeks.’

With this, he put heart and strength into every man, and they launched themselves in a mass at the Trojans, so that the ships echoed to the shouts of the Achaeans. And when the Trojans saw Patroclus and his charioteer in all their shining armour, they thought swift-footed Achilles had ended his quarrel by the ships, and now was reconciled; their hearts sank, and their line began to waver, and each man looked round anxiously to find a path of escape from utter ruin.

Patroclus it was who hurled the first glittering spear, right into the centre of the throng milling around the stern of brave Protesilaus’ ship, striking Pyraechmes, who had led his Paeonian horse-lords from Amydon and the banks of the broad Axius. He found the right shoulder, and backward Pyraechmes tumbled in the dust with a loud groan, while around him his comrades fled in panic, now Patroclus had killed their leader and champion. Sweeping them from the stern, the Greeks put out the fire, leaving the half-burnt vessel behind as they drove the Trojans in rout among the hollow ships, while the cries rose up to heaven.

As Zeus the Lightning-Gatherer drives dense cloud from the high summit of some great mountain, such that craggy peaks and lofty headlands with all their glades spring into view, and the sky grows clear to its very depths; so the Danaans drove the cloud of smoke and flame from their ships, and breathed more freely. Yet the battle continued, for the black ships were not yet purged of the Trojans, who still showed resistance, and gave ground to the Greeks, beloved of Ares, only when they must.

Then the Greek leaders each killed his man as the Trojan force was scattered. Mighty Patroclus pierced Areilycus in the thigh with a throw of his spear as he turned to run, driving the point clean through, so the bronze shattered the bone and Areilycus fell face-forwards on the ground. Warlike Menelaus thrust at Thoas and hit him in the chest, where the shield failed to protect him, loosening his limbs. Meges was too quick for the charging Amphiclus, striking through the thigh, where the muscle is densest, the spear-point tearing the sinews, and darkness shrouded his eyes. Nestor’s son, Antilochus, caught Atymnius with his spear’s keen blade, driving the bronze tip through his flank so he toppled forward. But Maris, nearby, angered by his brother’s death, charged at Antilochus with his spear, and straddled the corpse. Yet a second son of Nestor, godlike Thrasymedes, before his enemy could thrust, struck him deftly in the shoulder. The spear-blade sheared the ligaments at the base of the arm, and smashed the bone. He fell with a thud and darkness clouded his eyes. So these two brothers, vanquished by two, went down to Erebus. Spearmen they were, noble friends of Sarpedon, sons of Amisodarus: he who reared the monstrous Chimaera that brought grief to many a man.

Ajax the Lesser, son of Oïleus, too leapt into the throng where Cleobolus was impeded, taking him alive but swiftly ending his struggles with a blow to the neck from his sword. Its blade ran hot with blood, and over Cleobolus’ eyes fell the darkness of death and unyielding fate.

Next Peneleos met with Lyco, after their spear throws failed, both hurling them in vain, now clashing instead with swords. Lyco swung at the helmet ridge with its horsehair crest, shattering his sword at the hilt. But Peneleos struck at the neck beneath the ear, and the blade sliced through, leaving the head hanging to one side, held only by a piece of skin, as Lyco fell.

Meriones, running swiftly, overtook Acamas, wounding him in the right shoulder as he mounted his chariot. He fell to the ground and a mist veiled his eyes. Idomeneus too, with the merciless bronze, thrust at Erymas, struck him in the mouth so the spear passed clean through the skull, below the brain, and shattered the white bone, smashing the teeth, filling the eyes with blood. And blood spurted from nostrils and gaping mouth, as death’s black cloud enfolded him.

BkXVI:351-425 Patroclus routs the Trojans

So each of these Danaans killed his man, and the Greeks harried the Trojans, like hungry wolves battening on lambs or kids, snatching the young and weak from the hill-flock that some foolish shepherd allowed to scatter. The Trojans lost all heart, and took to tumultuous retreat.

Now mighty Ajax was keen as ever to hurl a spear at bronze-clad Hector, but the Trojan leader, skilled in war, his broad shoulders protected by his ox-hide shield, watched the whirring arrows and hurtling spears pass by. He knew the tide of battle was turning, but held on, anxious to save his loyal men.

Like a dark cloud from Olympus, when Zeus whips up a storm, that sails through the bright air to shroud the sky, so the noise of the Trojan rout spread from the ships, and they crossed the trench again in confusion. And now Hector was carried from the field, weapons and all, by his swift-footed team, leaving those trapped at the trench with no means of escape, the trench where many a pair of swift war-horses shattered the pole and left their master’s chariot behind.

Patroclus, slaughter in his heart, chased them down, calling fiercely to his Danaans, while the Trojans, their lines broken, filled the ways in tumultuous flight. A cloud of dust rose to the sky, as the straining horses sped towards the city from the ships and huts. Wherever he saw knots of men fleeing, Patroclus headed them off with a cry, others falling headlong from overturned chariots beneath his axle-trees. Those swift immortal horses the gods gave as a splendid gift to Peleus charged on and leapt the trench at a bound, as Patroclus’ heart urged him on towards Hector, but the Trojan leader’s team was swift and had carried him from the field. The rushing sound of the host of Trojan horses as they fled was like the mighty roar of the raging torrents that score the hillsides, as they race from the mountains to the sea laying waste the fields, when some tempest strikes the black earth in harvest time and Zeus sends violent rain, in anger against those who deliver corrupt judgements in free assembly, careless of divine vengeance and void of all justice.

Patroclus had now cut off the leading companies and pushed them back towards the ships denying them a path to the city in their panic. Between the ships, the high wall, and the river, he put them to the slaughter, avenging many a dead Danaan. There he killed Pronous first with a throw of his bright spear, taking him in the chest exposed by his shield, and loosening his limbs so he fell with a thud. Then he rushed at Thestor, son of Enops, who crouched in his gleaming chariot, his mind and senses lost, and the reins slipped from his hands. Patroclus struck him on the right of his jaw with the spear, driving it past the teeth, and pulling its shaft back dragged him over the chariot’s rim, like a man astride a jutting rock landing a mighty fish hooked on the end of his line. He hauled him from the chariot, gaping on the end of his spear then dropped him on his face as his life fled. Next, facing Erylaus’s attack, Patroclus hurled a rock that landed square on his head and split the skull apart in its heavy helmet so that the man fell prone on the ground, and death that devours the spirit cloaked him. Then, one after another, he left men dead on the black earth, Erymas, Amphoterus, and Epaltes, Tlepolemus son of Damastor, Echius, Pyris, Ipheus, Euippus, and Polymelus son of Argeas.

When Sarpedon saw his belt-less Lycians fall at the hands of Patroclus, he called out to the rest in reproach: ‘Shame on you, Lycians, where are you off to? Run then, quickly, while I face this fellow, and find out who it is that conquers all and hurts us so, killing so many of our noblest.’

BkXVI:426-507 The death of Sarpedon

So saying, he leapt fully armed from his chariot, and Patroclus seeing him do so did likewise. With loud cries, they attacked each other, like raucous vultures, fighting with curved beak and crooked talon on some high crag.

Zeus, gazing down on them, felt pity, and spoke to Hera his sister-wife: ‘Alas that Sarpedon, so dear to me, is fated to die at the hands of Patroclus! Even now I am undecided, whether to snatch him up and set him down alive in his rich land of Lycia, far from this sad war, or allow him to fall to this son of Menoetius.’

‘Dread son of Cronos,’ ox-eyed Queen Hera replied, ‘what do you mean? Are you willing to save a mortal from the pains of death, one long since doomed by fate? Do so, but don’t expect the rest of us to approve. And think hard about this fact too. If you send Sarpedon home alive, why should some other god not do the same for their dear son, and save him from the thick of war? Many who fight before Priam’s great city are children of immortals, and those divinities will resent it deeply. If he’s so dear to you, and it grieves your heart, let Patroclus defeat him in mortal combat, but after his spirit has departed, send Death and sweet Sleep to bear him away to the broad land of Lycia, where his brothers and all his kin may mark his resting place with barrow and pillar, a privilege of the dead.’

The Father of men and gods accepted her advice, but he sent a shower of blood-red raindrops to the earth, to honour his beloved son whom Patroclus would slay in the fertile land of Troy, far from his native realm.

Now, as the two warriors came face to face, Patroclus struck noble Thrasymelus, Sarpedon’s brave squire, piercing his lower belly, and loosening his limbs. But Sarpedon’s reply went astray, his gleaming spear striking the horse Pedasus on its right shoulder, and the horse cried out in pain breathing its last, and fell in the dust with a great sigh as it gave up its life. The other two horses pulled away, the yoke creaking with the strain, their reins entangled with the trace horse in the dust. But Automedon, the noted spearman, found an answer. Leaping down, and drawing the long sword from beside his sturdy thigh, he cut the trace horse loose in a moment. The other pair righted themselves, and tugged again at the harness, as the two men resumed their deadly duel.

Again Sarpedon’s bright spear missed, the blade passing over Patroclus’ left shoulder, leaving the man unscathed. But Patroclus hurled his bronze, in turn, and the spear sped from his hand and not in vain, striking Sarpedon where the ribs press on the beating heart. He fell as an oak, a poplar or lofty pine falls in the mountains, downed by the shipwrights with sharp axes as timbers for a ship. Down he tumbled, and lay stretched out at his horses’ feet, groaning and clutching the blood-stained dust before his chariot. There, struggling with death, the leader of the Lycian shieldmen, straddled by Patroclus, called out to his dear comrade: ‘Glaucus, my friend, warrior of warriors, now you must wield the spear and battle bravely; now if you truly have fight in you, let dread war be your aim. First go and rouse the Lycian leaders to battle now over Sarpedon. And you yourself must defend me with your spear. If the Greeks strip me of my armour, here where I fall close to the ships, then it will be a reproach and a cause of shame to you through all your days. Hold your ground with courage, and urge on the men.’

As he spoke death descended over his mouth and eyes, and Patroclus set his foot on his chest, and drew the spear from the flesh, the whole midriff yielding with it, releasing the point of the blade and Sarpedon’s spirit, while the Myrmidons held the panting horses, the creatures eager to flee now the chariots lacked their masters.

BkXVI:508-568 Glaucus rouses the Lycians and Trojans

Deep sorrow gripped Glaucus on hearing Sarpedon’s call: his heart was pained seeing no way to help him. Distressed by the arrow-wound that Teucer, fighting for his comrades’ lives, had dealt him, as he charged the Achaean wall, he gripped his damaged arm with his other hand. He prayed though to Apollo, the Far-Striker: ‘Lord, hear me wherever you are, in Lycia’s rich land perhaps or even here in Troy, for you always hear a man in sorrow, as I sorrow now. The wound I have is grievous, my arm a mass of pain; the blood will not clot, the shoulder is numb. I can’t grip my spear to fight to the enemy. And Sarpedon, son of Zeus, the best of us is gone, for Zeus cannot even save his own child. Heal me of this foul wound, Lord Apollo, ease my pain, give me the strength to rally my Lycians, rouse their courage, and fight over the body of the fallen.’

So he prayed, and Apollo heard, quelling the pain, clotting the black blood flowing from the deep wound, and filling his heart with courage. Glaucus recognised immortal aid, glad of the god’s swift answer. He ran to rally the Lycians, and urge them to fight for Sarpedon’s corpse, then sought the Trojan leaders, Polydamas, son of Panthous, noble Agenor, Aeneas and bronze-clad Hector. He found the latter and addressed him with winged words: ‘Hector, you forget your allies now, we who are spending our lives for you, far from our friends and our native land. You give not a thought to their protection. Sarpedon has fallen, chief of the Lycian shield-men, the strong and just defender of Lycia. Bronze-clad Ares has brought him down at the point of Patroclus’s spear. Take your stand, beside his body, friends, dread the breath of shame if the Myrmidons, in anger over those Danaan dead we slew with our spears by the swift ships, strip him of his armour and desecrate his corpse.’

The Trojans were gripped by a deep intolerable sorrow, for Sarpedon though from a far country was a mainstay of their army, as much for his eminence in warfare as for the host of men he brought with him. Hector, in his anger, took the lead as they charged savagely towards the Greeks. But brave Patroclus, son of Menoetius, spurred the Achaeans on. He called to the Aiantes, both already filled with zeal: ‘Now, my lords, drive off the foe, and prove as brave as ever, no, braver still. Sarpedon, who breached our wall, is dead. Let’s take the corpse, strip it of its armour, mangle the flesh and slay with the merciless bronze any of his friends who try to save it.’

He spoke to the willing. Then both sides, strengthening their numbers, met in battle with a mighty roar, the Trojans and Lycians, the Myrmidons and Achaeans, fighting over the body of the fallen, their battle gear clanging. And Zeus wrapped the fog of war about the fierce conflict, so that the vicious toils of battle might wreathe his dear dead son.’

BkXVI:569-683 The fight over Sarpedon’s body

At first the Trojans repelled the fierce Achaeans, killing one of the best of the Myrmidons noble Epeigeus, son of brave Agacles. He had been king in populous Budeum, but having killed a noble kinsman had found sanctuary with Peleus and silver-footed Thetis. They sent him with Achilles, breaker of battle lines, to horse-taming Troy to fight against the Trojans. He had just laid hands on the body when glorious Hector struck him on the head with a stone, shattering the skull inside the heavy helm, so he fell, face down, on the corpse, and death that takes the spirit embraced him. Then Patroclus was plunged in grief for his dead friend, and he swept through the front line swift as the falcon that scatters jackdaws and starlings. Straight at the Lycians and Trojans, you flew, Patroclus, master horseman, your heart filled with wrath at your comrade’s death. Sthenelaus, he killed, dear son of Ithaemenes, striking his neck with a stone, tearing the sinews, and the front line led by glorious Hector gave ground. As far as a man, trialling his strength perhaps or attacked by bloodthirsty foes in battle, can hurl a long javelin the Trojans withdrew before the Achaean advance. Then Glaucus, leading the Lycian shield-men, turned and killed bold Bathycles, beloved son of Chalcon, who lived in Hellas, first among Myrmidons in wealth and land. Glaucus, spinning round on him as Bathycles tried to overtake him, struck the man deep in the chest with a blow of his spear. He fell with a thud, and the Greeks were overcome with grief at the fall of a worthy warrior, while the Trojans rejoiced, and ran in to surround the corpse.

But the Achaeans, full of courage still, advanced towards their foe. Meriones it was who killed Laogonus, brave son of Onetor the priest of Idaean Zeus, honoured by the people like a god. He struck the fully armoured warrior beneath the jaw by the ear, and his spirit fled from his body, and the hated dark descended. Then Aeneas replied hurling his bronze-tipped spear at Meriones hoping to catch him as he came forward covered himself with his shield. But Meriones was on the alert and avoided the missile, stooping low so the long spear fell to earth behind him, and fixed itself quivering in the ground until the mighty war-god stilled its fury. Aeneas enraged, shouted out angrily: ‘Meriones, fine dancer that you are, if that had struck your dancing days were done.’

And Meriones, the famous spearman, replied: ‘Aeneas, you may be strong, but even you can’t kill everyone who attacks you, not if they know how to defend themselves. You too are mortal, I think. If I aimed well enough with my keen spear, strong as you are and trusting in your strength, still the glory would soon be mine and you on your way to Hades the Horse Lord.’

At this, great Patroclus reproached him: ‘Meriones, fine warrior that you are, why waste time on words? Speeches, good friend, won’t drive the Trojans from Sarpedon’s body. The earth will take not a few of us before that moment comes, so less words and more action, the fate of this struggle is in our hands, keep your oratory for the council.’

With this, he led a charge, and godlike Meriones followed. Then the beaten earth sent up a din of bronze and leather, of solid shields, like the resounding echo of axe-men in the mountain glades, while the warriors thrust at one another with keen swords and double-edged spears. No friend of his would have known the face of noble Sarpedon, veiled as he was from head to foot by dust and gore and lost in a hail of missiles. Round the corpse the warriors swarmed, as flies in the farmyard hum round the brimming pails, at milking time in spring. And Zeus fixed his gleaming eye on the desperate conflict, gazing down and reflecting on Patroclus’ fate, whether as they struggled over godlike Sarpedon noble Hector should kill him with his sword, and strip the armour from him, or whether more men should die first, in the toils of battle. And in the end he thought it best that Achilles’ powerful comrade should drive bronze-clad Hector and the Trojans further towards the city, while wreaking greater havoc.

First he stirred Hector to sorry flight. He leapt to his chariot and calling to the Trojans led the rout, knowing that Zeus had tipped the sacred balance against them. Then the brave Lycians yielded ground, and they too were driven off, having seen their king struck to the heart, and left among the dead, for many had fallen there as the son of Cronos tightened the net of that vicious conflict. From Sarpedon’s shoulders the Greeks stripped the gleaming bronze armour, and bold Patroclus left his men to bear it back to the hollow ships.

Now it was that Zeus, the Cloud Gatherer, called to Apollo: ‘Dear Phoebus, go now and carry Sarpedon out of range of the battle, and cleanse the black blood from his body, then lift him to some distant place, bathe him in running water, anoint him with ambrosia, clothe him in imperishable garments, and give him to those twin brothers Sleep and Death, who bear men swiftly away. They will soon set him down in the broad rich lands of Lycia. There his brothers and all his kin will bury him beneath barrow and pillar, since the dead are owed that privilege.’

Apollo promptly obeyed his father’s words, speeding towards the sound of bitter conflict from the heights of Ida. At once he bore noble Sarpedon far from the war, bathed, anointed and clothed him, and gave him over to Sleep and Death to carry to the broad rich Lycian lands.

BkXVI:684-725 Apollo directs the fight before the city

Patroclus, now, ordered Automedon to whip the horses on in pursuit of the Trojans and Lycians, in a fit of blind foolishness! Had he obeyed Achilles’ advice he’d have escaped dark death, and an evil fate, but the will of Zeus is greater than man’s will, and even a brave man he may readily cause to panic, robbing him of glory, and just as readily inspire a man to fight. He it was who now filled Patroclus with rashness.

Who then was the first to fall to you, Patroclus, and who the last, when the gods drew you to your death? The first were Adrastus; Autonous, Echeclus, Perimus son of Megas, Epistor, Melanippus, Elasus, Mulius, and Pylartes. These were the first he killed and the rest thought only of flight.

Then the sons of Achaea would have captured Troy of the lofty gates, behind the wide-ranging spear of fierce Patroclus, if Phoebus Apollo has not mounted the high wall to aid the Trojans and seek the warrior’s ruin. Three times Patroclus scaled an angle of the lofty wall, and three times Apollo hurled him down, his immortal hands thrusting away his glittering shield. And when, as if possessed, he mounted yet a fourth time Apollo checked him with a dreadful cry: ‘Withdraw, Zeus-born Patroclus, I say your spear is not fated to capture noble Troy, nor is that of your master Achilles!’

At this, Patroclus fell back a goodly distance, to avoid Apollo the Far-Striker’s wrath.

Meanwhile Hector had reined in his horses at the Scaean Gate, unsure whether to wheel them back into the conflict, and fight, or order his men back behind the walls. While he debated Phoebus Apollo appeared, in the strong and active figure of Asius, brother to Hecabe and horse-taming Hector’s uncle. He was the son of Dymas the Phrygian, who lived beside the Sangarius. So disguised, Apollo, the son of Zeus, addressed him: ‘Why have you left the field, Hector? You should be there. I wish I were stronger again than you as I am weaker, and I’d teach you not to shirk your duty. Come now, hunt down Patroclus with that splendid team, and hope with Apollo’s help to kill him and win glory.’

BkXVI:726-776 The fight over Cebriones’ body

With this, the god returned to the field of battle, while Hector turned to warlike Cebriones and ordered him to whip up the horses. Now Apollo, in the midst brought blind panic on the Argives, and paved the way for Hector and the Trojans. The rest of the Greeks Hector left alone, making no efforts to attack them, instead, with his powerful team, chasing down Patroclus. Patroclus at bay leapt from his chariot, his spear in his left hand, a large jagged gleaming stone clutched in his right. Planting his feet firmly, his fear of his foe swiftly dispelled, he hurled it with perfect aim, and struck Hector’s charioteer, Cebriones, a natural son of great Priam, in the forehead, as he grasped the reins. The stone crushed his brow, shattering the bone, and his eyeballs fell in the dust at his feet. He plunged like a diver from the sturdy chariot, and his spirit fled his bones. Then Patroclus, tamer of horses, how you mocked him: ‘There, what an acrobat, how skilfully he dives! So perfectly executed he’d do a fine job aboard ship, fishing oysters from teeming depths, despite the weather. The Trojans it seems make good divers too.’

With this he flung himself at the dead warrior, like a lion wounded in the chest while ravaging a farm, a victim of its own daring. So you leapt for Cebriones, Patroclus.

For his part, Hector too leapt from his chariot, and the two fought over the corpse, like mountain lions on the heights struggling over a hind, each as ravenous and spirited as the other. Over Cebriones, those two of the loud war-cry, Hector and Patroclus, tried eagerly to pierce each other’s flesh with the merciless bronze.

Hector grasped the body by its head, and held on tight, while Patroclus gripped the feet as hard, and round them the Greeks and Trojans swirled in mighty combat. Like the East and South winds, buffeting each other, shaking the depths of some mountain glade, whirling long boughs of beech and ash and smooth-barked cornel together, with a vast roar and the crack of breaking branches, so the Greeks and Trojans battered and slew each other, with never a thought on either side of yielding. A host of sharp spears bristled in the earth round Cebriones, and a host of feathered arrows sent twanging from the bow, while huge stones bounced from the shields of the struggling men. But he lay in the dust, sublime in his great fall, no longer mindful of his horsemanship.

BkXVI:777-867 The death of Patroclus

So long as the sun was high in the sky, the volleys of missiles found their mark, and men fell, but when it sank low at that hour when ploughmen unyoke their oxen, the Greeks proved masters of their fate. They dragged Cebriones’ corpse away from the Trojans and, beyond the clash of arms, stripped it of its armour. Then Patroclus was minded to destroy the Trojans. Three times that peer of swift Ares attacked them, shouting his dread war-cry, and each time killed nine men. But when, like a god, you charged at them again, Patroclus, then your fate loomed in sight. For Apollo met you, terrible in combat.

Apollo advanced, veiled in a dense mist, invisible to Patroclus in the tumult, stood behind him and struck him in the back with the flat of his hand. The warrior’s vision spun, as Apollo knocked the helmet from his head, sending it under the horses’ feet with a clang, and the plumes on its crest were streaked with blood and dust. The gods had never allowed it to be fouled till then, that horsehair-plumed helmet that protected the godlike brow and head of Achilles: now Zeus let Hector wear it for a while, since death was nearing him too.

The long-shadowed spear, thick, heavy and strong, and tipped with bronze, in Patroclus’ hands was wholly shattered, the tasselled shield on its strap fell to the ground, and that blow from Lord Apollo, son of Zeus, had loosened the breastplate. Then Patroclus’ mind was dimmed, his noble limbs were slack beneath him, and dazed he stood there. A Dardanian, Panthous’ son Euphorbus, the best spearman, horseman and runner of his generation, who had brought down twenty charioteers in this his apprenticeship in war, now cast his sharp spear and struck Patroclus in the back between the shoulders. He was first to hurl his spear, not killing you, horse-tamer Patroclus, but pulling the ash spear from your flesh and running back into the throng, fearing to stand and fight you, unarmed now though you were. And Patroclus, stunned by the god’s blow and Euphorbus’ spear, retreated into the Myrmidon ranks, dodging fate.

But Hector, seeing brave Patroclus withdraw, struck by the blade, made his way to him through the ranks, and drove at him with his spear, piercing the lower belly and ramming the point home. Patroclus fell with a thud, to the grievous sorrow of the Achaean army. As a lion in the high mountains may fight with a tireless wild boar over a trickling stream from which both seek to drink, and conquers his panting enemy by strength alone, so Hector, Priam’s son, overcame the valiant son of Menoetius, who himself had killed so many men, and striking him close at hand with his spear robbed him of his life. Then straddling him, he shouted in victory: ‘I think you boasted you’d sack our city, Patroclus, take our women captive, sail with them to your native land. How foolish! Hector and his swift horses are here to fight for them, Hector the finest spearman among the warlike Trojans, I who shield them from the day of doom, while as for you, the vultures shall have you. Even Achilles, with all his valour, could not save you, wretched man, though I don’t doubt he told you as you left, for he chose to stay: “Patroclus, master horseman, don’t return to the hollow ships till you’ve pierced the tunic at man-killing Hector’s chest and drenched it in his blood.” No doubt that’s what he said, and you in your madness though it would be so.’

But though your strength was ebbing fast, horse-taming Patroclus, yet you answered: ‘Boast, while you can, Hector, for Zeus and Apollo it was who gave you victory. They conquered me: they stripped the armour from my shoulders. If twenty men like you had faced me alone, all would have died at the point of my spear. But Fate the destroyer and Apollo, Leto’s son, have conquered: only then came Euphorbus the mortal, while you are but the third to claim my life. This I tell you: and go brood upon it. You indeed have only a little while to live, even now death approaches and your fixed destiny, to fall at the hands of Achilles, peerless scion of Aeacus.’

With these words death took him, and his spirit, loosed from his limbs, fled down to Hades, bemoaning its fate and leaving youth and manhood behind. But dead though he was, noble Hector still replied: ‘Patroclus, what makes you so sure of my swift destruction? Who knows but Achilles, son of fair-haired Thetis, may be struck by my spear first, and lose his life?’

With this, he planted his heel on the warrior’s body, drew the spear from the wound, and thrust the corpse away, to fall on its back. Then he launched himself with the spear at Automedon, godlike squire of fleet-footed Achilles, grandson of Aeacus. He was keen to strike him down, but the swift team swept Automedon away, those immortal steeds, the glorious gifts the gods gave Peleus.