Homer: The Iliad

Book I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk I:1-21 Invocation and Introduction

- Bk I:22-52 Chryses invokes Apollo

- Bk I:53-100 Achilles and Calchas speak

- Bk I:101-147 The argument begins

- Bk I:148-187 Agamemnon and Achilles quarrel

- Bk I:188-222 Athene counsels Achilles

- Bk I:223-284 Nestor speaks

- Bk I:285-317 Nestor’s advice ignored

- Bk I:318-356 Agamemnon seizes Briseis

- Bk I:357-427 Achilles complains to Thetis, his mother

- Bk I:428-487 Chryses’ daughter is returned

- Bk I:488-530 Thetis pleads with Zeus

- Bk I:531-567 Hera opposes Zeus

- Bk I:568-611 Hephaestus calms his mother Hera

BkI:1-21 Invocation and Introduction

Goddess, sing me the anger, of Achilles, Peleus’ son, that fatal anger that brought countless sorrows on the Greeks, and sent many valiant souls of warriors down to Hades, leaving their bodies as spoil for dogs and carrion birds: for thus was the will of Zeus brought to fulfilment. Sing of it from the moment when Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, that king of men, parted in wrath from noble Achilles.

Which of the gods set these two to quarrel? Apollo, the son of Leto and Zeus, angered by the king, brought an evil plague on the army, so that the men were dying, for the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses the priest. He it was who came to the swift Achaean ships, to free his daughter, bringing a wealth of ransom, carrying a golden staff adorned with the ribbons of far-striking Apollo, and called out to the Achaeans, above all to the two leaders of armies, those sons of Atreus: ‘Atreides, and all you bronze-greaved Achaeans, may the gods who live on Olympus grant you to sack Priam’s city, and sail back home in safety; but take this ransom, and free my darling child; show reverence for Zeus’s son, far-striking Apollo.’

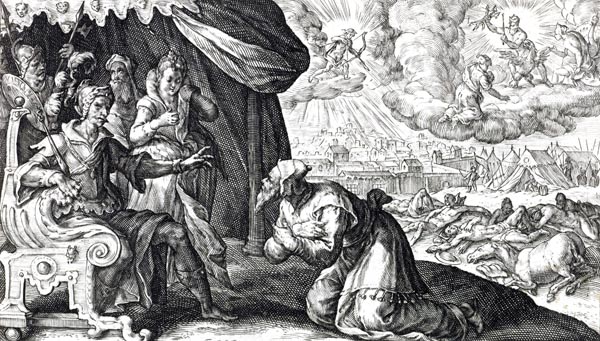

‘Chryses begs Agamemnon for his daughter’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

Bk I:22-52 Chryses invokes Apollo

Then the rest of the Achaeans shouted in agreement, that the priest should be respected, and the fine ransom taken; but this troubled the heart of Agamemnon, son of Atreus, and he dismissed the priest harshly, and dealt with him sternly: ‘Old man, don’t let me catch you loitering by the hollow ships today, and don’t be back later, lest your staff and the god’s ribbons fail to protect you. Her, I shall not free; old age will claim her first, far from her own country, in Argos, my home, where she can tend the loom, and share my bed. Away now; don’t provoke me if you’d leave safely.’

So he spoke, and the old man, seized by fear, obeyed. Silently, he walked the shore of the echoing sea; and when he was quite alone, the old man prayed deeply to Lord Apollo, the son of bright-haired Leto: ‘Hear me, Silver Bow, protector of Chryse and holy Cilla, high lord of Tenedos: if ever I built a shrine that pleased you, if ever I burned the fat thighs of a bull or goat for you, grant my wish: Smintheus, with your arrows make the Greeks pay for my tears.’

So he prayed, and Phoebus Apollo heard him. Down he came, in fury, from the heights of Olympus, with his bow and inlaid quiver at his back. The arrows rattled at his shoulder as the god descended like the night, in anger. He set down by the ships, and fired a shaft, with a fearful twang of his silver bow. First he attacked the mules, and the swift hounds, then loosed his vicious darts at the men; so the dense pyres for the dead burned endlessly.

‘Apollo’ - Hendrick Goltzius, 1588

Bk I:53-100 Achilles and Calchas speak

For nine days the god’s arrows fell on the army, and on the tenth Achilles, his heart stirred by the goddess, white-armed Hera, called them to the Place of Assembly, she pitying the Danaans, whose deaths she witnessed. And when they had assembled, and the gathering was complete, swift-footed Achilles rose and spoke: ‘Son of Atreus, if war and plague alike are fated to defeat us Greeks, I think we shall be driven to head for home: if, that is, we can indeed escape death. But why not consult some priest, some prophet, some interpreter of dreams, since dreams too come from Zeus, one who can tell why Phoebus Apollo shows such anger to us, because of some broken vow perhaps, or some missed sacrifice; in hopes the god might accept succulent lambs or unmarked goats, and choose to avert our ruin.’

He sat down again when he had spoken, and Calchas, son of Thestor, rose to his feet, he, peerless among augurs, who knew all things past, all things to come, and all things present, who, through the gift of prophecy granted him by Phoebus Apollo, had guided the Greek fleet to Ilium. He, with virtuous intent, spoke to the gathering, saying: ‘Achilles, god-beloved, you ask that I explain far-striking Apollo’s anger. Well, I will, but take thought, and swear to me you’ll be ready to defend me with strength and word; for I believe I’ll anger the man who rules the Argives in his might, whom all the Achaeans obey. For a king in his anger crushes a lesser man. Even if he swallows anger for a while, he will nurse resentment till he chooses to repay. Consider then, if you can keep me safe.’

Swift-footed Achilles spoke in reply: ‘Courage, and say out what truth you know, for by god-beloved Apollo to whom you pray, whose utterances you grant to the Danaans, none shall lay hand on you beside the hollow ships, no Danaan while I live and see the earth, not even if it’s Agamemnon you mean, who counts himself the best of the Achaeans.’

Then the peerless seer took heart, and spoke to them, saying: ‘Not for a broken vow, or a missed sacrifice, does he blame us, but because of that priest whom Agamemnon offended, refusing the ransom, refusing to free his daughter. That is why the god, the far-striker, makes us suffer, and will do so, and will not rid the Danaans of loathsome plague, until we return the bright-eyed girl to her father, without his recompense or ransom, and send a sacred offering to Chryse; then we might persuade him to relent.’

Bk I:101-147 The argument begins

When he had finished speaking, Calchas sat down, and Agamemnon, the warrior, royal son of Atreus, leapt up in anger; his mind was filled with blind rage, and his eyes blazed like fire. First he rounded on Calchas, with a threatening look: ‘Baneful prophet, your utterance has never yet favoured me; you only ever love to augur evil, never a word of good is spoken or fulfilled! And now you prophesy to the Danaan assembly, claiming the far-striker troubles them because I refused fine ransom for a girl, Chryses’ daughter, and would rather take her home. Well I prefer her to my wife, Clytaemnestra, since she’s no less than her in form or stature, mind or skill. Yet, even so, I’d look to give her up, if that seems best; I’d rather you were safe, and free of plague. So ready a prize at once, for me, I’ll not be the only one with empty hands: that would be wrong: you see for yourselves, my prize now goes elsewhere.’

Then swift-footed Lord Achilles spoke in answer: ‘Great son of Atreus, covetous as ever, how can the brave Achaeans grant a prize? What wealth is there in common, now we have shared our plunder from the cities which cannot be reclaimed? Give up the girl, as the god demands, and we Achaeans will compensate you, three or four times over, if Zeus ever lets us sack high-walled Troy.’

Then Lord Agamemnon answered him: ‘Brave you may be, godlike Achilles, but don’t try to trick me with your cleverness. You’ll not outwit me or cajole me. Do you think, since you demand I return her, that I’ll sit here without a prize while you keep yours? Let the great-hearted Achaeans find a prize, one that’s to my taste, so the exchange is equal. If not, then I myself will take yours, or seize and keep that of Ajax or Odysseus. Whoever it is, he’ll be angered. But we can ponder all of that later; for now, let us launch a black ship on the shining sea, crew her, and embark creatures for sacrifice and this fair-faced daughter of Chryses too. One of our counsellors can go as captain, Ajax, Idomeneus, noble Odysseus or you, son of Peleus, you the most redoubtable of men, and make sacrifice and appease far-striking Apollo.’

Bk I:148-187 Agamemnon and Achilles quarrel

Then, with an angry look, swift-footed Achilles replied: Why, you shameless schemer, why should any Achaean leap to obey your orders to march or wage war? No quarrel with Trojan spearmen brought me here to fight: they have done me no wrong. No horse or cow of mine have they stolen, nor have my crops been ravaged in deep-soiled Phthia, nurturer of men, since the shadowy mountains and the echoing sea lie between us. No, for your pleasure, you shameless cur, we followed to try and win recompense, for you and Menelaus, from the Trojans. And you neither see nor care; and even threaten to rob me of my prize, given by the sons of Achaea, reward for which I laboured. When the Achaeans sack some rich Trojan city, it’s not I who win the prize. My hands bear the brunt of the fiercest fight, but when the wealth is shared, yours is the greater, while I return, weary with battle, to the ships, with some small fraction for my own. So now I’m for Phthia, since it’s better to lead my beaked ships home than stay here dishonoured piling up wealth and goods for you.’

Agamemnon, king of men, answered him then: ‘Be off, if your heart demands it; I’ll not beg your presence on my account. Others, who’ll honour me, are with me: Zeus, above all, the lord of counsel. Of all the god-beloved princes here you are most odious to me, since war, contention, strife are dear to you. If you are the greatest warrior, well, it was some god I think who granted it. Go home, with your ships and men, and lord it over the Myrmidons: I care naught for you, or your anger. And here’s my threat: since Phoebus Apollo robs me of Chryses’ daughter, a ship and crew of mine will return her, but I’ll pay your quarters a visit myself, and take that prize of yours, fair-faced Briseis, so that you know how my power exceeds yours, and so that others will think twice before claiming they’re my peers, and comparing themselves to me, face to face.’

Bk I:188-222 Athene counsels Achilles

While Agamemnon spoke, the son of Peleus was gnawed by pain, and the heart in his shaggy breast was torn; whether to draw the sharp blade at his side, scatter the crowd, and kill the son of Atreus, or curb his wrath and restrain his spirit. As he pondered this in his mind, his great sword half-unsheathed, Athene descended from the sky, sent by Hera, the white-armed goddess, who loved and cared for both the lords alike. Athene, standing behind the son of Peleus, tugged at his golden hair, so that only he could see her, no one else. Achilles, turning in surprise, knew Pallas Athene at once, so terrible were her flashing eyes. He spoke out, with winged words, saying: ‘Why are you here, daughter of aegis-bearing Zeus? Is it to witness Agamemnon’s arrogance? I tell you and believe that this son of Atreus’ will pay soon with his life for his insolent acts.’

The goddess, bright-eyed Athene, replied: ‘I came from the heavens to quell your anger, if you’ll but listen: I was sent by the goddess, white-armed Hera, who in her heart loves and cares for you both alike. Come, end this quarrel, and sheathe your sword. Taunt him with words of prophecy; for I say, and it shall come to pass, that three times as many glorious gifts shall be yours one day for this insult. Restrain yourself, now, and obey.’

Then swift-footed Achilles, in answer, said: ‘Goddess, a man must attend to your word, no matter how great his heart’s anger: that is right. Whoever obeys the gods will gain their hearing.’

So saying he checked his great hand on the silver hilt, and thrust the long sword back into its sheath, obeying the word of Athene; she meanwhile had left for Olympus, for the palace of aegis-bearing Zeus, and rejoined the other gods.

Bk I:223-284 Nestor speaks

But, angered still, the son of Peleus, once more turned on Atreides with bitter taunts: ‘You drunkard with a cur’s mask and the courage of a doe, you’ve never dare to take up arms and fight beside your men, or join the Achaean leaders in an ambush. You’d sooner die. You’d rather steal the prize from any Achaean in this great army who contradicts you. Devourer of your own people you are, because they are weak, or else you, Atreides would have perpetrated your last outrage. But I say true, and swear a solemn oath See this staff, that will never leaf or sprout again now it is severed from its mountain branch, doomed never to be green again, stripped by the bronze adze of its foliage and bark, now borne in their hands by the Achaean judges who defend the laws of Zeus: I swear, on this, a solemn oath to you, that a day will surely come when the Achaeans, one and all, shall long for Achilles, a day when you, despite your grief, are powerless to help them, as they fall in swathes at the hands of man-killing Hector. Then you will feel a gnawing pang of remorse for failing to honour the best of the Achaeans.’

‘Dispute between Achilles and Agamemnon’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

So spoke the son of Peleus, flung down the gold-studded staff, and resumed his seat; while, opposite, Atreides raged at him. But then soft-spoken Nestor rose, the clear-voiced orator of Pylos, from whose tongue speech sweeter than honey flowed. He had already seen the passing of two mortal generations born and reared with him in holy Pylos, and now he ruled the third. He spoke to the assembly, then, with benevolent intent: ‘Well, here is grief indeed to plague Achaea. How Priam and his sons would rejoice, and the hearts of the Trojan throng be gladdened, if they could hear this tale of strife between you two, the greatest of Danaans in war and judgement. You are both younger than I, so listen, for I have fought beside warriors, better men than you, who ever showed me respect. I have never seen the like of them since, men such as Peirithous, and Dryas, the people’s Shepherd, Caeneus, Exadius, godlike Polyphemus, and Aegeus’ son Theseus, one of the immortals. They were the mightiest of earth-born men; the mightiest and struggled with the mightiest, the Centaurs that lair among the mountains, whom they utterly destroyed. They summoned me, and I joined them, travelling far from Pylos. I held my own among them, though against them no man on earth could fight. Yet they listened to my words, and followed my advice. You too should do the same, for that is wise. Great as you may be, Atreides, do not seek to rob him of the girl, leave him the prize that the Achaeans granted; and you Achilles, son of Peleus, do not oppose the king blow for blow, since the kingly sceptre brings no little honour to those whom Zeus crowns with glory. You have your power, a goddess for a mother, yet he is greater, ruling over more. Agamemnon, quench your anger, relent towards Achilles, our mighty shield against war’s evils.’

Bk I:285-317 Nestor’s advice ignored

‘Old man, indeed you have spoken wisely’, replied Agamemnon. But this man wants to rule over others; to lord it, be king of all, and issue orders, though I know one who will flout him. What though the immortal gods made him a spearman; does that give him the right to utter such insults?’

Achilles then interrupted, saying: ‘A coward, and worthless, I’d be called, if I gave way every time to you no matter what you say. Command the rest if you wish, but give me no orders, I’ll no longer obey. And here’s another thing for you to think on: I’ll not raise a hand to fight for the girl, with you or any other, since you only take back what you gave. But you’ll take nothing else of mine by the swift black ships, against my will. Come, try, and let these men be witness: your blood will flow dark along my spear.’

When their war of words was over, they both rose, and so ended the gathering by the Achaean ships. Achilles left for his fine fleet and his huts, with Patroclus, son of Menoetius, and his men; while Agamemnon launched a swift ship in the waves, chose twenty oarsmen, and embarked an offering for the god, then sent the fair-faced daughter of Chryses aboard, with Odysseus, that man of resource, to take command.

While they embarked and set sail on the paths of the sea, Atreides ordered his men to purify themselves, and wash the dirt from their bodies in salt-water, and offer Apollo a sacrifice of unblemished bulls and goats, by the restless waves; and the savour went up to heaven with trails of smoke.

Bk I:318-356 Agamemnon seizes Briseis

Though the camp was busy with all this, Agamemnon did not forget his quarrel with Achilles, or his threats, and he summoned his heralds and trusty attendants, Talthybius and Eurybates, saying: ‘Go to Achilles’ hut, seize the fair-faced Briseis and bring her here. If he refuses to release her, I’ll go in force to fetch her, and so much the worse for him.’

With this stern command, he sent them on their way, and unwillingly the two made their way along the shore of the restless sea, till they came to the ships and huts of the Myrmidons. They found Achilles seated by his black ship, by his hut, and it gave him no pleasure to see them. Seized by fear and awe of the king, they stood silently; but he in his heart knew their unspoken request, and said: ‘Welcome, heralds, you ambassadors of Zeus and men, approach me. You bear no guilt, only Agamemnon, who sends you here for Briseis. Come, Patroclus, divinely born, bring out the girl, and hand her to these men. If ever there is need of me to save the Greeks from disaster, let them bear witness to this before the blessed gods, mortal men and that shameless king. His mind raves destructively, indeed, and he fails to look behind him or foresee what might save his Achaeans in the coming fight beside the ships.’

At this, Patroclus obeyed his order, and leading fair-faced Briseis from the hut, handed her to the heralds, who returned beside the line of Achaean ships, with the unwilling girl. But Achilles withdrew from his men, weeping, and sat by the shore of the grey sea, gazing at the shadowy deep; and stretching out his arms, passionately, prayed to his dear mother: ‘Since you bore me to but a brief span of life, Mother, surely Olympian Zeus the Thunderer ought to grant me honour; but he grants me none at all. I am disgraced indeed, by that son of Atreus, imperious Agamemnon, who in his arrogance has seized and holds my prize.’

BkI:357-427 Achilles complains to Thetis, his mother

Tearfully, he spoke, and his lady mother heard him, in the sea’s depths, where she sat beside her aged father. Cloaked in mist she rose swiftly from the grey brine, and sitting by her weeping son caressed him with her hand, and spoke to him calling him by name: ‘Child, why these tears? What pain grieves your heart? Don’t hide your thoughts; speak, so I may share them.’

‘Thetis’ - Hendrick Goltzius, 1588

Then swift-footed Achilles sighed heavily and spoke: ‘You must know; why need I tell the tale to you who know all? We sacked Thebe, Eetion’s sacred city, and brought back all the spoils, which the Achaeans shared out fairly between them, choosing the fair-faced daughter of Chryses for Agamemnon. Then Chryses, the priest of far-striking Apollo, came to the swift ships of the bronze-clad Greeks to free his daughter with a rich ransom, bearing far-striking Apollo’s ribbons on a golden staff, and begged her freedom of the Achaeans, chiefly the Atreidae, leaders of armies. The Greeks called out their wish, to respect the priest and accept the fine ransom, but this displeased Agamemnon who sent him packing, and with a stern warning. So, angrily, the old man returned, and Apollo, who loved him dearly, heard his prayer, and fired arrows of evil at the Argives. Then men died thick and fast and the god’s darts rained down on the broad camp. At last a seer with knowledge uttered the archer god’s true oracle. I was the first to urge them, there and then, to propitiate the god, but anger gripped that son of Atreus, swiftly he rose and threatened what now has come to pass. Bright-eyed Achaeans in a fast ship are bearing the girl to Chryse with offerings for the god; while heralds have taken from my hut another girl, Briseis, my prize from the army, and led her away. If you have power, come now, to your son’s aid; ask help from Zeus on Olympus, if ever you warmed his heart by word or deed. Often I heard you, in my father’s halls, claim proudly that you alone of the immortals saved Zeus, son of Cronos, lord of the storm, from a vile fate when those other Olympians, Hera, Poseidon, and Pallas Athene, planned to bind him fast. Goddess, you swiftly summoned, to high Olympus, the hundred-handed monster whom gods call Briareus, and men Aegaeon, mightier than his father Poseidon; and you saved Zeus from those bonds. For Briareus seated himself, in his strength, beside that son of Cronos, and the sacred gods in fear left Zeus alone. Kneel beside Zeus, and clasp his knees, remind him of that, in hope he might now choose to help the Trojans, pin down the Achaeans among their ships, slaughter them on the shore, so they may reap their king’s reward, and imperious Agamemnon may realise his blindness (ate) in dishonouring the best of the Greeks.’

Bk I:428-487 Chryses’ daughter is returned

‘Oh, my son,’ Thetis sadly replied, ‘is it for this I bore you, unlucky in my labour? Since your life is doomed to be brief, filling so short a span, if only it were your fate to stay by the ships, free of pain and sorrow; but you, more wretched than other men, must meet an early death; such is the painful destiny for which I brought you into this world. Yet I’ll go myself to snowy Olympus, and tell the Thunder-bearer Zeus what you have said, hoping that he will hear me. Sit by your swift sea-going boats, meanwhile, nurse your anger against the Achaeans, hold back from the fight; for Zeus has left for Ocean’s stream, to banquet with the peerless Ethiopians, and all the gods go with him; but twelve days hence he returns to Olympus, and then I’ll cross the bronze threshold of his palace, kneel at his feet, and I think persuade him.’ With this, she left him to his anger, caused by their seizing of that lovely girl, against his will.

Meanwhile Odysseus had touched at Chryse, bearing the sacrifice. Entering the deep harbour, they furled the sail and stowed it in the black ship, dropped the mast by lowering the forestays, and rowed her to her berth. Then they cast out the anchor stones, made fast the hawsers, and leapt on shore. Next, the offering of cattle for far-striking Apollo was disembarked, and Chryses’ daughter landed from the sea-going boat. It was Odysseus, that man of resource, who led her to the altar, and handed her to her dear father, saying: ‘Chryses, our leader Agamemnon commanded me to return your daughter, and make holy sacrifice to Phoebus for all the Greeks, and propitiate your lord Apollo, who has brought the Argives pain and mourning.’ With this, he handed her to her father who joyfully clasped her in his arms.

Swiftly now they tethered the offering of cattle around the well-built altar, rinsed their hands and took handfuls of sacrificial barley grains. Then Chryses raised his arms and prayed on their behalf: ‘Hear me, God of the Silver Bow, protector of Chryse and holy Cilla, lord of Tenedos. Just as once before when I prayed to you, you honoured me and struck the Achaeans a fierce blow, so grant my new plea, and avert this dreadful scourge from the Danaans.’ So he prayed, and Apollo listened.

When they had offered their petition and scattered grains of barley, they drew back the victims’ heads, slit their throats and flayed them. Then they cut slices from the thighs, wrapped them in layers of fat, and laid raw meat on top. These the old man burnt on the fire, sprinkling over them a libation of red wine, while the young men stood by, five-pronged forks in their hands. When the thighs were burnt and they had tasted the inner meat, they carved the rest in small pieces, skewered and roasted them through, then drew them from the spits. Their work done and the meal prepared, they feasted and enjoyed the shared banquet, and when they had quenched their first hunger and thirst, the young men filled the mixing-bowls to the brim with wine and pouring a few drops first into each cup as a libation served the gathering. All that day the Achaeans made music to appease the god, singing the lovely paean, praising the god who strikes from afar; while he listened with delight.

And at sunset as darkness fell, they lay down to sleep by the ships’ cables, and when rosy-fingered Dawn appeared they sailed for the distant camp of the Achaeans. Then far-striking Apollo sent them a following wind, and they raised the mast and spread the white sail. The canvas bellied in the wind and the dark wave hissed at the stern, as the boat gathered way and sped through the flood, forging on its course. So they came to the broad camp of the Achaeans, dragged the black vessel high on shore, and propped her with lengths of timber, then dispersed among the huts and ships.

Bk I:488-530 Thetis pleads with Zeus

But swift-footed Achilles, heaven-born son of Peleus, still nursed his anger beside the swift ships. He avoided the Assembly where men win renown, and kept from battle, eating his heart out where he was, longing for the noise of battle.

At dawn on the twelfth day, the company of immortal gods, led by Zeus, returned to Olympus. Thetis had not forgotten her promise to her son, and at morning, emerging from the waves, she rose to the broad sky and Olympus. There she found Zeus, he of the far-thundering voice, sitting apart on the highest peak of ridged Olympus. She sank in front of him, clasped his knees with her left arm, raised her right hand to touch his chin, and so petitioned the son of Cronos: ‘Father Zeus, if ever I helped you by word or deed, grant me this wish, honour my son, who is doomed to die young. For Agamemnon the king shows disrespect, arrogantly seizing his rightful prize. Avenge my son, Olympian Zeus, lord of justice; enhance the Trojans’ power, till the Greeks honour and respect my son and make amends.’

Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, made no reply to her words, he sat there silently. But Thetis, still clasping his knees, clung to him and pleaded again: ‘Make me this promise faithfully, and nod your head, or else refuse, for I am powerless, then I shall know how little I am honoured here.’

Zeus, the cloud-lord, deeply troubled, said: ‘This is a sorry business, indeed, and you will force a quarrel with Hera. She will taunt and rile me. As it is, she scolds me endlessly before the other gods, claiming I aid the Trojans in battle. Go now, before she notices, while I think the matter through. Come, I will nod my head, to reassure you, since you immortals know this as my sure pledge; once I give the nod, my word can never be recalled, it proves true and is fulfilled.’

So spoke the son of Cronos, inclining his shadowed brow till the ambrosial locks, on the King’s immortal head, stirred together, and high Olympus shook.

Bk I:531-567 Hera opposes Zeus

So ended their meeting, and Thetis plunged from gleaming Olympus to the briny deep, while Zeus left for his palace. There the company of gods rose to their feet in deference to their father; none daring to stay seated at his entry, all standing as one. He took his royal place, but Hera, watching, could not fail to know that silver-footed Thetis, daughter of the Old Man of the Sea, had pleaded with him. At once she goaded Zeus, Cronos’ son: ‘What immortal has sought your counsel, arch-deceiver? It’s ever your delight to work behind my back, and make all your decisions in secret. When did you ever openly discuss your plans with me?’

‘Hera’ - Hendrick Goltzius, 1588

‘Hera’ replied the father of men and gods, ‘do not expect to know all my thoughts: though you are my wife you would find it a burden. Whatever it is right for you to hear, no immortal, no human, shall know before you; but of what I plan without reference to the gods, make no question, do not ask.’

‘Dread son of Cronos,’ the ox-eyed queen replied, ‘what is this? I have never questioned you, nor asked: you have ever peace to think on what you wish. But now my heart fears silver-footed Thetis, daughter of the Old Man of the Sea, has swayed you; for she knelt by you at dawn and clasped your knees. Dare I imagine that you bowed to her, gave her a firm pledge of support for Achilles, and promised slaughter by the Greek ships?’

Then cloud-gathering Zeus replied: ‘You’re obsessed, forever brooding. I can hide nothing from you, yet you’ll achieve nothing too, only estrange us, and so much the worse for you. If things are as you think, then is it not because I wish them so? Now sit there, quiet, and obey me; lest I set my all-powerful hands on you, and all the gods of Olympus lack the strength save you.’

Bk I:568-611 Hephaestus calms his mother Hera

At this, the ox-eyed queen trembled, restrained herself and sat down silently. All the immortal gods there were troubled, and it was Hephaestus, famed for his skill, who broke the silence, hoping to calm his mother, white-armed Hera: ‘This is a sorry business. It’s intolerable you two should quarrel over a mortal, and set the gods at odd with one another. What joy in a good banquet if animosity prevails? I advise my mother, who herself knows this is best, to make peace with our dear father, Zeus, lest he reprimand her again and our feast be ruined. What if the Olympian lord of lightening, mightiest of us all by far, should choose to blast us where we sit! Mother, speak gentle words to him, and the Olympian will once more show us grace.’

So saying, he hurried to his dear mother, and placed a two-handled cup in her hands: Be patient, mother, and contain your anger, lest you who are dear to me are beaten while I look on. For all my pain, there’s no way I could help you, the Olympian is a tough antagonist to face. Once before, when I rushed to save you, he seized me by the foot and hurled me from heaven’s threshold; all day headlong I plunged, and fell, with the sun, half-dead, to Lemnos’ shore. There the Sintians ran to nurse me from my fall.’

The white-armed goddess, Hera, smiled at this, and took the cup from her son, still smiling. Then he served wine to all the other gods, starting on the left, pouring sweet nectar from the mixing-bowl. And immortal laughter rose from the bliss-filled gods, as they watched Hephaestus bustling about the hall.

So they banqueted all day till sunset, missing nothing of the shared feast, nor of the lovely lyre Apollo played, nor of the singing Muses, who answered each other in sweet harmony.

But when the sun’s bright light had faded, each went off to rest in their separate houses, built with rare skill by the god lamed in both feet, famous Hephaestus; and Olympian Zeus, the lord of lightning, ascended to his accustomed bed to find sweet sleep, with Hera of the golden throne beside him.