Storming Heaven

A. S. Kline

V - Donne

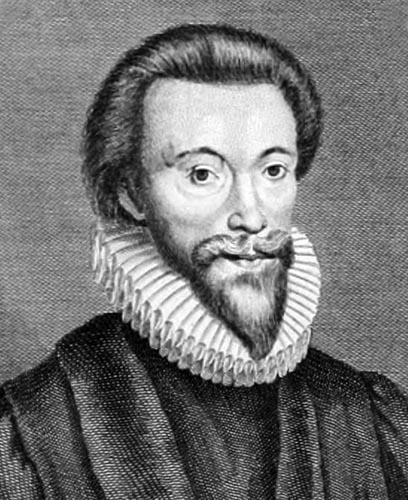

‘John Donne (W. Skelton sculp)’

Lives of Dr. John Donne (1796) - Sir Henry Wotton, Mr. Richard Hooker, Mr. George Herbert and Dr. Robert Sanderson

by Walton, Izaak, 1593-1683 Zouch, Thomas, 1737-1815

Internet Archive Book Images

Elizabeth adhered to her middle way in religion, maintaining the split from Rome that her father had instigated, embracing a Protestant theology, and punishing religious views which attempted either to move the Church towards the Lutheran and Calvinist positions or to demand that it revert to Catholicism. The Catholic agitators were hunted and persecuted. They vanished into the shadows. Apolitical Catholic adherence was expressed in private or in art, in refuge or in metaphor. To be part of a Catholic family, as John Donne was, meant entering the world with a liability, a potential source of discrimination and risk.

Born in 1572, he was in his twenties as Essex and Raleigh jostled for position, just twenty-one when Marlowe died. Out of the first, Elizabethan, half of his life rises a new and startling voice, his ‘muse’s white sincerity’ expressed in a private, intelligent, linguistically demanding form of verse. It reveals initially a young man defending himself against the world. He was nominally a Catholic, sensitive and unsure of his reception in a hostile society. He was a poet, with deep feelings, alert to rejection by an unknown public. He became a wearer of masks. In his Satires and Elegies, in an attempt to act out identity, he adopted witty, apparently insensitive roles, but in his poems addressed to friends, and in the Epithalamion of 1595, he broke through to deeper feelings. Then in the Songs and Sonnets he made that inward turn towards intimacy, with love as the great subversive theme, which seems essentially ‘modern’ because it is, for us, essentially serious. Like Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Raleigh, the intellect behind the poetry overcomes the limitations of existing form and thought, to speak authentically.

Shakespeare’s deepest note is his inner sweetness and tenderness; Marlowe’s his restless desire for something beyond, for the extreme; Raleigh’s his sensitivity to transience, his silvery elegiac quality; Donne’s is intimacy, his focus on the individual life, on the self. He is the first truly autobiographical poet in English, the first in whom the emotions and events of the life are vitally presented in the content of the verse, though often indirectly and elusively.

Donne was interested in the self’s changeability and inconstancy, in the instability that was part of his character and temperament. Loyalty, constancy, disloyalty, betrayal, pledges and oaths are of the scenery of love, but also vital elements of his life. A man brave in words, who found it difficult to sustain that courage in actions. A man who could stand firm in his loyalty to a woman, but relinquish his religious allegiance. Who could write verse about faithlessness and spend the second half of his life in the embrace of faith. This centring on the volatile self makes Donne an innovator in literature, ‘Copernicus in poetry’, someone who changed the line of sight from man moving in orbit around the world and society, to the world and society reflected and centred on man. Part of this shift was an internalisation of sacredness, the creation of an inner temple, the making of ‘one little room, an everywhere’. Part of it was a retreat, a defence, a response to his practical difficulties in achieving a role in life. Part of it was the vitality of his intellect, a sensitivity to his own inner world and responses. Part of it was the reality of love in his own life, its dominance over him, his need for its consolation, to be ‘taken and bound with a kiss’. It mirrored the movement within society towards Protestant individualism with the ancient values enshrined primarily within marriage and the personal life. At the same time his own nature was oriented in its sensitivities, towards love as the ultimate sacrament, the ultimate seriousness of a life. If not religious love then secular, if not secular then religious, since all love is one.

There are echoes of Saint Augustine in Donne, the echoes of a life starting in secular love and ending in religious love, of Augustine’s fascination with the self and with time, of the confessional tendency in his mind, of the change in him from rebellion to orthodoxy. ‘I loved not yet,’ says Augustine, ‘yet I loved to love. I sought what I might love, in love with loving.’ Donne begins with the desire and searches for the goal, testing his way among loyalties and betrayals, endeavouring to understand love as well as to preach it, posturing and inventing, but ultimately discovering and achieving. He explores in the world of verse the tensions of love, the paradoxes and confusions of love, the mysteries and sacraments of love, the pains of love’s loss and love’s betrayal, the challenge to the self’s isolation which is love.

Donne also feared aspects of his own selfhood, its melancholy, its isolation, its pain, its terrors, and tried always to connect, to be ‘a part of the main’. ‘What torment is not a marriage bed to this damnation, to be secluded eternally, eternally, eternally from the sight of God?’ he cries out in a sermon of 1622. It is resonant with that speech of Mephistopheles in Faustus ‘Hell hath no limits nor is circumscrib’d in one self place; for where we are is hell, and where hell is, must we ever be.’ He appears to have lacked an intuitive grasp of human relations, to have found relationship difficult, to have found it hard to escape the island of himself. There is nevertheless that thread of love in his life, which he follows tenaciously.

Like Theseus the clue was handed to him always by a woman. The labyrinth was always his own selfhood, the Minotaur his own fears, desires and unformed humanity. Theseus’s betrayal of Ariadne, the Goddess, is his betrayal. But as if to compensate for his disloyalties his new pledges once made are lifelong, and in friendship, marriage, parenthood and the established Church, he found a warmth and solace.

Donne, as has been said, came of a Catholic family, his father dying young, his mother remarrying. She was the daughter of John Heywood, musician and author and descendant of Sir Thomas More, who had been executed forty years before Donne’s birth. Catholic persecution was growing more severe. Being a Catholic was a risk, a constraining factor in achieving worldly success and grounds for mistrust and suspicion. Marlowe, Raleigh, Essex were non-Catholics. A dissenting attitude might be tolerated in them as Protestants. Donne and Shakespeare however, as well as reflecting the deep myths of Catholicism in their writings – the misunderstood and powerless human life, the primacy of Love, the silent all-suffering Goddess – lived guardedly for the most part. Both were conservative and conformist in their later lives, sometimes to an uncomfortable degree. It is not an accusation of cowardice to say that they shied away from the social reality of what was happening to the old religion. Both died in the new English faith. To adhere to the Catholic religion and be deeply involved with its political destiny would have required exceptional belief and commitment.

Donne’s background was not easy to escape. He was educated at home by Catholic tutors. His uncle Jasper Heywood was leader of the secret Jesuit mission to England, and was captured, imprisoned and tried when Donne was eleven years old. When Donne was twenty-one, in a period of considerable anti-Catholic activity his brother Henry was arrested for harbouring a Catholic priest, and died in Newgate of the plague. It was in May of 1593, the month of Marlowe’s death. The priest was hanged, drawn and quartered in the following year. In 1612 his stepfather was imprisoned in Newgate for refusing to swear the Oath of Allegiance, by which time Donne had left the Catholic Church. Donne’s earliest portrait at eighteen, a private miniature, shows him with cross-shaped ear-rings, in a Spanish looking style, with the motto in Spanish ‘Antes muerto que mudado’, ‘Sooner dead than changed’. It was a declaration of loyalty to Catholicism that would have done him little good if it had been openly displayed.

He followed a prudent path of education, going with his younger brother Henry to Hart Hall, Oxford, where the absence of a chapel made it easier to conceal lack of public worship, and then to Cambridge. By 1592 he was at Lincoln’s Inn as a law student, adopting the masks and poses of his early writings. He portrays himself as the mercenary seducer, the cruel and lewd cynic, and then with a change of voice satirises the vices and corruption of Court and society. Later in life he saw it as a time of sinfulness, like Augustine who, in his Confessions, declared ‘I came to Carthage, into the hissing cauldron of unholy loves’. In a close parallel to Donne, Augustine condemned that period when ‘for nine years from nineteen to twenty-eight I was led astray, and led others astray myself in turn.’ Perhaps the errors of this time, that Donne condemned later, were those of a fundamentally moral man adrift, fearing rejection, and isolation, responding with social and verbal aggression, those ‘satiric fires which urged me to have writ in scorn of all’, to the world where he longed for admittance.

Already his great theme was Love, and there is a tender voice, even where it is sometimes the voice of the seducer, in much of the early verse. He is already ‘inquiring of that mystic trinity... body, mind and Muse.’ He is already in ‘love’s hallowed temple’, subverting religious language or in a deeper sense offering it to the service of those ‘mystic books’, the manifestations in the flesh of the Goddess.

Though Donne inherited the stigma of Catholic adherence he himself wanted to achieve social position. His education, at Oxford, Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn, equipped him for public office, and created amicable contacts that might assist him to a career, ‘that short roll of friends writ in my heart’. At Oxford he met Henry Wotton, who was later secretary to Essex, and English Ambassador in Europe. Wotton became a link with Essex, and Francis Bacon’s circle. Like Donne, Wotton went with Essex on the Cadiz and Islands expeditions of 1596 and 1597. The voyages with Essex, where he would also have seen Raleigh at close quarters, consolidated his friendship with Thomas Egerton, the son of Elizabeth’s Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, whom he had met at Lincoln’s Inn. And, through the son’s influence perhaps, in 1597, Donne became Secretary to the Lord Keeper and moved to York House by the Thames. It was the crucial period of his early life.

He was inside the citadel of power. Egerton had himself been a practising Catholic, and that may have eased the way for Donne despite his family connections. He was within the walled Garden of the Elizabethan establishment, and in York House, with its own walled gardens down to the river, doubly enclosed. If he worked hard and loyally, and conformed to the requirements of his employment, he had a solid future ahead. Already wavering in his Catholic faith (‘inconstancy unnaturally hath begot a constant habit’ he wrote later of his own ‘devout fits’) he embraced the Protestant religion as Egerton had done. It meant leaving behind the difficult Catholic world, rejecting family allegiances, redirecting his own innermost instincts, his own worship of the Goddess, in a requirement to conform.

In his Paradoxes and Problems he had put forward the proposition ‘that all things kill themselves’. As far as his career was concerned that was what he proceeded to do. In Egerton’s household he found the fifteen year old Ann More, Lady Egerton’s niece, daughter to Sir George More, a descendant also of Sir Thomas More. The Garden enclosed the lovers, secretly and dangerously, as the Elegies describe. ‘Thou angel bring’st with thee a heaven like Mahomet’s paradise.’ The clandestine affair involved deep emotions and they made a firm commitment to each other, ‘where my hand is set my seal shall be’. In a terrible breach of faith for a man in Donne’s position within the household, consummating a relationship with the young girl, without the knowledge of her father, or her aunt (‘close and secret as our souls, we have been’) they carried on their ‘long-hid love’. He writes that he taught her ‘the alphabet of flowers’ which ‘might with speechless secrecy deliver errands mutely, and mutually’ and, wreathing religious and sexual metaphor together in a statement of how he saw himself influencing her mind and body, declared ‘I planted knowledge and life’s tree in thee’. He had ‘with amorous delicacies refined thee into a blissful paradise.’

Despite the poses, the later recriminations, and Donne’s ambiguous attitude to the female sex, those ‘daughters of Eve’, Ann More was the recipient of his life’s love. So much so that in his later religious life he found immense difficulty in re-channelling his emotions towards divine love and away from her memory. She was the incarnate Goddess, as the religious imagery of the poetry testifies. There is more than a conceit in employing the metaphors. Only an unintelligent man could use them without knowing the psychological depth of their meaning. In the private world of his poetry, and he was an immensely self-protective and private man, he replays the hidden nature of their love, in the concealed paradise of imagination and creativity.

Their relationship picked up the echoes of the adulterous and forbidden, of Tristan and Iseult, of that love ‘which all love of other sights controls’. ‘The secret song was her marvellous beauty’ wrote the poet Gottfried, of Iseult. That heresy of the greater personal love was Donne’s first allegiance in his life. It is a test of courage to affirm one’s own experience against the world, the glory of secular love against the sacraments of institutionalised society. It is a part of that assertion of the individual life out of which once came personal rights and liberty, the secular state and the freedoms of the individual within it. It was part of that Copernican shift of emphasis that Donne made, from the social order to the individual as the true end of being. It requires in its sensual as well as its intellectual loyalties, a union of mind and body. ‘All here in one bed lay’ he says. ‘She is all states, and all princes, I, nothing else is.’ Of the Sun, in a counter-Copernican thought ‘this bed thy centre is, these walls thy sphere’.

Nature and the earthbound lover can be one, against society and the social order, lay and ecclesiastical. The song that Heloise and Isolde sang was the song of that inner rapture, of erotic and personal values, hidden away temporarily in a Celtic, in a Medieval world. It differed fundamentally from the Greek achievement of social and ethical values linked together in the cool light of the marketplace and the assembly. ‘Nous avons perdu le monde et le monde nous’ Iseult says to Tristan. ‘Seek we then ourselves in ourselves’ Donne wrote in his youth ‘so we, if we into ourselves will turn.... may outburn the straw, which doth about our hearts sojourn.’ ‘Know’ he writes to a male friend ‘that I love thee, and would be loved.’

Through his poetry run the puns on Ann’s name, even in verses written after her death. He is the man who ‘after one such love, can love no more’ and she is ‘more than Moon’. And, fancifully, Ann More is Ana, an ancient name of the Goddess, Ovid’s Anna Perenna, the eternal. In Ireland the Goddess was this beneficent Ana, a title of the Goddess Danu, mother of the Danaan gods of the Celts. Earlier she was Inanna, or Nana, a name of the Sumerian Goddess Ishtar, and later she was Christianity’s St Anne the mother of the Virgin. Ann More becomes an incarnation of the Triple Goddess, that goddess of love, sexuality and death who makes the undercurrent, the hidden spring, in Donne’s life and work, and whom he cannot truly renounce even in the self-constriction of his final religious years. And she is Eve before the Fall.

Sometime, in the spring of 1598 or 1599, occurs the engraving of his name on a window at York House, which is described in his poem A Valediction: of my name in the Window. The poem itself was probably written in 1600. The dating depends on the words ‘love and grief their exaltation had’ which refer to the astrological ‘exaltations’ of Venus and Saturn which occurred at this time. The poem refers to events within the time of Ann More’s presence at York House, and plays on her name. The window glass is ‘more, that it shows thee to thee, and clear reflects thee to thine eye’, and the cut name will make her ‘as much more loving, as more sad’. It is written to assert Donne’s commitment to her through ‘love’s magic’ that makes them one, to express mock fears over her constancy, and to testify to their ‘firm substantial love.’ To read it tenderly is I think to read it correctly. The Good Morrow, The Canonization, The Anniversary, a whole cluster of the Songs and Sonnets, express this love for her in varying ways, in the loving, intimate, skilful poetry which must have satisfied, in its creation, both his heart and his head.

Through it runs the theme of inconstancy, the preoccupation with ‘lover’s contracts’ that indicates his deep inner fears of rejection. Part of its power depends on its poise, between the scepticism, even cynicism, that there could be faithfulness in love, and an overt tenderness, which re-asserts the possibility, and the faith. Donne tests and affirms his own belief. In The Relic he summons up the full wealth of religious metaphor, bordering on the sacrilegious, to transmit the ‘miracles we harmless lovers wrought’ beyond the grave. ‘All measure, and all language, I should pass should I tell what a miracle she was.’

In September 1599 Donne carried the sword at the funeral of his friend Thomas, Egerton’s son, who, taking part in the oppressive Elizabethan military operations in Ireland, died of wounds incurred in Essex’s service. At the end of that year Essex, banished from Court after his ride from Ireland to Nonesuch, was confined to York House, under Egerton’s control. Essex was ill of ‘the Irish flux’, in depression, eating little and sleeping less. Donne wrote, from Whitehall in his all-pervading religious metaphor, that Essex was ‘no more missed here than the angels which were cast down from heaven, nor (for anything I see) likelier to return.’

Essex’s illness may have been a contagious infection since in January 1600, Lady Egerton died, plunging the house into mourning. Egerton himself neglected his business for some time. Ann More went home to Losely Park, and to her father, Sir George. Essex was sent off to his own Essex House still under house arrest. The lovers were parted. In the poem ‘Twickenham Gardens’ Donne expressed his grief and anxiety, ‘blasted with sighs, and surrounded with tears, hither I come to seek the spring’. The verse worries at the issue of female constancy and clearly pre-dates his marriage. He is the ‘self-traitor’ who brings love and ‘the serpent’ sexuality into ‘true paradise’, playing on double-meanings, since, at Twickenham, Bacon had laid out the type of landscaped ‘paradise’ described in his essay ‘Of Gardens’. It was Essex who had granted Bacon Twickenham Park and Gardens in 1594 (the land was recalled in 1601). Donne would probably have had access through his friend Wotton who was Essex’s secretary.

Donne had been one of the contributors of poems to a poetic debate on the merits of court, country and city life of which, among others, Bacon’s and Wotton’s contributions survive. Donne though he studied at Lincoln’s Inn and not Gray’s, where Bacon had studied, may still have been one of the group of young men whom Bacon met with at Twickenham to make verses. Donne would probably have come into contact with Bacon during Donne’s and Essex’s time at York House (Bacon’s birthplace, which he was later to regain under James). Though Twickenham passed into the hands of Lucy, Countess of Bedford, a later patroness in 1607, the poem makes little sense in relation to her, but every sense if written in 1600.

It also employs a language echoed in verses to the Countess of Huntingdon written close to this time. She was Elizabeth Stanley whose mother the Countess of Derby, Egerton now married. She came to York House in late 1600. The verses pick up the theme of Paradise and the Fall, and the vocabulary of sighs, woman’s scorns, crystal and fountain, and the freezing lover who ‘talks to trees’. The theme of Paradise and the Fall was uppermost in his mind at this time and in early 1601 as that strange poem The Progress of the Soul, dated 16th August 1601, testifies. In the epistle which precedes it and the poem, the spider, and the serpent appear again, and ‘that apple which Eve eat’. The soul progresses through its upwards climb from plant, to animal, to woman, (and, it was intended, ultimately to Donne himself) with a good deal of unorthodox sexual commentary along the way. Through his affair with Ann More, he perhaps felt he had fallen in more than one sense, but did not yet guess the consequences of that fall.

In February 1601 the Essex rebellion took place, closely followed by Essex’s arraignment and execution. Donne, as a secretary, must have been occupied with the Essex trial and its aftermath, since Egerton was responsible for the arrangements. He may have witnessed Francis Bacon displaying his disloyalty to his old master, Essex, in acting for the prosecution. It was a fine lesson in avoiding the dangers of too much commitment, and in the politic fluidity of allegiance required in meeting the needs of ambition.

Donne became Member of Parliament for Brackley, a borough in the pocket of the Lord Keeper, and in October 1601 as Parliament assembled Sir George More brought Ann back to London. Donne married her secretly, without Sir George’s knowledge ‘about three weeks before Christmas’.

She was seventeen, still a minor, he twenty-nine. They were either blind to the consequences, or they were hopeful that a fait accompli would have to be accepted by More and Egerton. More was furious, demanded Donne’s dismissal of Egerton, and Donne was briefly imprisoned in the Fleet. His career was in ruins. His letter of 2nd February 1602 to More apologises for not seeing Sir George face to face because of illness (a lack of courage also?) and tries to set out the ‘truth and clearness of this matter between your daughter and me’. ‘So long since as her being at York House, this had foundation, and so much then of promise and contract built upon it, as without violence to conscience might not be shaken. At her lying in town this last Parliament, I found means to see her twice or thrice. We both knew the obligations that lay upon us, and we adventured equally.’

This is the language of their shared vows. Donne could not have anticipated the full consequences of their action, may have subsequently regretted it, and been left trying to argue their case with Sir George. Equally their great love may have made it an inescapable choice for them both, and the result may have been inevitable. Donne argues that they had ‘honest purposes in their hearts and those fetters in our consciences’, that she is one for whom ‘I tender much more than my fortunes or life, (else I would I might neither joy in this life, nor enjoy the next). ‘As my love is directed unchangeably upon her, so all my labours shall concur to her contentment’. He then tries to lever More into acceptance of the situation. ‘That it is irremediably done; that if you incense my Lord (Egerton) you destroy her and me; that it is easy to give us happiness, and that my endeavours and industry, if it please you to prosper them, may soon make me somewhat worthier of her.’ Sir George seems to have relented, but Egerton refused to reinstate Donne. The great love had cost him dear in worldly terms. It added force to a negative aspect in his attitude towards women, which often appears in his later writing.

They had been expelled from the Garden; therefore Ann More was also Eve. Ann More was a daughter of Eve; therefore they had been expelled from the Garden. The Goddess is ambivalent; she is, as a personification of Nature, both the creator and the destroyer, the temptation and the fulfilment. Woman is both the sacred Temple, and the great betrayer. Yet ‘all those oaths which I and thou have sworn, to seal joint constancy’ were sworn on both sides, those ‘oaths made in reverential fear of love’ bound both parties to the contract. Donne knew that ‘Oh, to vex me, contraries meet in one’, knew that instability in himself that found it hard to rise above the results of his own actions, and to endorse reality ‘for better or worse’.

Through their great love he makes himself an extraordinary precursor of modern, secular love, where the sacredness of life and nature may be defended inwardly, now that the external myths of the Goddess and the God are indeed merely part of mythology. But through his adherence to the old damaging Christian views of the Fall, mythologically potent, he becomes an ordinary man of his age, a devaluer of Woman, and of his own courage to choose love. It disappoints us in him, looking from our secular age where part of the battle to establish a saner view of the sexes has been fought through. It disappoints us in our view of human rights, in an age which eventually may even get as far as the true rights of all creatures. It disappoints us in our sense of love, its primary value to us, its encapsulation of what is deepest in us, originating in the creatures from which genetically we descend (and ascend), in their nurture, empathy, and endurance. Our values may be biologically adaptive, may indeed be the result of the workings of the indifferent genetic mechanism, but they are still our core and a world that we can endorse if we choose.

Donne fails to rise above sexuality at those moments, and fails to endorse the sacred marriage, to endorse those positive aspects of the primal Goddess, which are the sources of our deepest values. He fails to be true, or sensitive or kind. His later attempt to transfer his love to his Christ and his God can indeed seem an evasion of his essential self. Nevertheless, though his ambivalence becomes all pervasive, the love remains.

In the terms of his own age his attitudes were nothing remarkable. That was how Woman was perceived in a Protestant religious sense. He merely acquiesced in that social suppression of the dying Goddess, dying in the waning powers in England of the Catholic Church, dying in the person of the aged Queen Elizabeth, and by doing so was part of that process which confirmed the Protestant age. The elements in Christianity that were paramount were not Christ’s life and his values in action in the world. They were precisely the rebellion of the sinful angels; the creation and the temptation of man; the fall, the incarnation, the atonement through crucifixion for the sins of the world; and the resurrection and regeneration through a saviour. Donne’s deepest sense is of the confessional, in a Protestant and not in a Catholic sense, seeking redemption after death, rather than in life. It explains his death-obsession, beyond the sexual ‘little death’, and into that death ‘we die in earnest, that’s no jest’, which Raleigh and Essex also understood.

Donne’s astrological chart at this moment of his life is symbolically interesting. His own attitude to astrology was probably that of Saint Augustine who in his Confessions explained his own first enthusiasm for books of astrology, but who received the advice from a man of understanding to throw them away as there were more important things to do. Asking for an explanation of astrology’s seeming ability to foretell the future, Augustine was told ‘the only possible answer that it was all due to chance.’ Augustine’s later writings reiterated the element of coincidence rather than interpretative skill, and he used the example of identical twins with near-identical birth charts, but differing lives, to dismiss astrology. With a little ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ however we can consider the symbolic elements of his chart.

Donne lived for two Saturn returns. The first when he was aged twenty-nine was the moment of his marriage, the second the time of his death. Halfway in between the two, came Ann’s death. Saturn was in Scorpio at his birth, in the sign of powerful feelings and emotions, imagination and subtlety, sexuality and passionate intensity. Saturn is the planet of despondency, sorrow, and proneness to ill health. Saturn is also the planet of duty and constraint. Saturn’s dogmatism and endorsement of intolerant laws is significant in Donne’s later religious phase while Scorpio plumbs the depths of feelings, almost obsessively.

Pluto the ruler of Scorpio was in Pisces. The planet of fate, the subconscious, the inner mind, was therefore in the religious sign of the fish, which is secretive, weak-willed, emotional, sensitive, compassionate, and impressionable.

Neptune the planet of poetry, of spirituality and idealism, of religious and artistic creativity was in Gemini, Mercury’s Sign, the place of mind and wit of linguistic flair and intellectual capability. ‘His fancy was inimitably high’ said Isaac Walton in his 1640 biography of Donne, ‘equalled only by his great wit, both being made useful by a commanding judgement.’ Neptune however is also self-deceiving, deceitful, unworldly, and Gemini is changeable, restless, inconsistent, living on nervous energy.

The uncertainty in the date of Donne’s birth does not allow much interpretation of his chart, but these influences on a whole generation certainly fit Donne’s life and psychology. The intellectual and witty poetry, the secretive, passionate nature, the religious depths, the later conformity and narrowness, the changeability that he recognised in himself, the compassion that Isaac Walton described. ‘He was by nature highly passionate, but more apt to reluct at the extremes of it. A great lover of the offices of humanity, and of so merciful a spirit, that he never beheld the miseries of mankind without pity and relief.’

Saturn, that planet in exaltation with Venus, which had overseen the writing in the window glass, returned to Scorpio at the time of his marriage, when he was nearly thirty, ‘to my six lustres almost now outwore’ as the Progress of the Soul expresses it. As with Marlowe, the Saturn return was fateful. Venus, planet of love, was also in Scorpio, opposing Uranus the planet of change, while Mercury, the mind, was square the deep feelings of the female Moon. It was a fateful marriage. Saturn was unaspected, uncertain, ambiguous. Pluto, Neptune, and Mercury were in a Grand trine to each other, reinforcing the fruitful and powerful tension of poetry, mind and fate. Neptune was sextile his natal Neptune, favourable for the arts. Mars, his sexual and life energy, was square the Sun of his fortunes, prophesying difficult times. Saturn is his signifier planet, potent at key times in his life, fatefully linked to the other planets again at his death.

Woman is both creator and destroyer. The marriage for Donne is also linked to sacrifice, a destructive fire. He hovers between the two perspectives of his mind, that which saw the perfection and beauty and sacredness of love, and that which embraced it as the fall of Man, the corruption of spirituality lost in sexuality, the erosion of the higher powers in the little death. That is the Protestant even Puritan position. It is with his attitude to women, to his own wife, whom he also loved, that he can lose our modern sympathies so completely. And yet he is never far from the accepted orthodoxies of his own age. Our criticism can only be of a man who having seen the possibilities of secular love, having enshrined the dying Goddess in his own heart, inwardly, fell back into the commonplace prejudices of his society. We feel unreasonably perhaps that he reneged, that he trampled on something sacred, that he failed as a man and as a mind, while retrieving his own place in his society, and, in his opinion, his own salvation. A harsh judgement. If he had not written the Songs and Sonnets would we criticise him merely for being a man of his times? But he reached the heights, and we judge him by the highest standards.

‘I was led astray’ writes Augustine. ‘I was in love with beauty of a lower order, which pulled me down.’ ‘I was bound down by this disease of the flesh. Its deadly pleasures were a chain I dragged behind me, but I feared to be free of it.’ ‘Why has the common opinion afforded women souls?’ asks Donne in one of his Problems ‘for even their loving destroys us’. ‘For the great soul’, he says in the Progress of The Soul ‘ had first in paradise, a low, but fatal room... Man all at once was there by woman slain, and one by one we’re here slain o’er again by them. The Mother poisoned the well-head, the Daughters here corrupt us, rivulets, no smallness ‘scapes, no greatness breaks their nets, She thrust us out, and by Them we are led astray.... She sinned, we bear; part of our pains is, thus to love them, whose fault to this painful love yoked us.’ This is orthodox theology, oppressive and dispiriting orthodox theology.

Did Donne, with one half of his mind, love the woman he married and, with the other half, hate her for ruining his career? Yet they had ‘adventured equally’. Was she, as in Shakespeare’s terrible dual vision, both the Great Goddess and the ravening witch? One moment the beloved Desdemona, the next condemned. One moment the despised Cordelia, the next the sacred silent image, echoed also in the last plays? Donne, in his life, mirrors Shakespeare’s tragic protagonists in theirs. They see the two-faced image of the Goddess, she who is reviled, and she who is worshipped.

That the theme is so potent in both men indicates its place in the life of their age. This was the compassionate Goddess of Catholicism, the sweet silence at the heart of Nature, and the God recoiling in antagonism and revulsion. This was the dark contrast between Woman seen as the Virgin Mary, the holy Mother, and Woman seen as Eve, the seductress, who precipitated the Fall of Man. ‘The sphere of our loves is sublunary;’ says Donne in one of his sermons ‘upon things naturally inferior to our selves.... It may be said that, by one woman, sin entered, and death, and that rather than by the man.... the woman being deceived, was in the transgression....the Virgin Mary had not the same interest in our salvation, as Eve had in our destruction.’ Elsewhere he says ‘She was not taken out of the foot to be trodden upon, nor out of the head to be an overseer of him; but out of his side, where she weakens him enough, and therefore should do all she can, to be a helper.’

Donne expresses in his life, the dual vision. He progresses from intimacy to religion, from revelation to orthodoxy. In one half of his mind is the heresy of the body, the heresy of secular love, of the sacred marriage internalised, of that freedom from society and from repression which sexuality, love, and intimacy offer. In the other half of his mind is the entangler, the White Goddess in her orgiastic phase, the ‘spider, Love’. This is not only the collision of two great mythical systems, that of the ancient pagan Mother Goddess, and that of Judeo-Christianity. It also has its roots in the primal, primitive relationship between men and women, in Man’s fears, and Woman’s power to give birth, Man’s attraction and Woman’s right to withhold, Man’s physical capabilities and Woman’s relational ones. Protestantism sought to resolve it by a sanctification of marriage and a demystification of society.

The primitive is always latent in us, woven into the genetic material, into the language of our inheritance, into the psyche. Shakespeare makes the step from exhibiting the primal conflict, the drama, to resolution of it in the sacred marriage protected by magical arts. Donne likewise ends in Anglican orthodoxy. As his marriage dies with Ann’s death, so Donne seems to die into a narrow religious answer. (When she died it was said that he was ‘crucified to the world’). Did the fear of rejection overpower him? Did he reinterpret the past in a travesty of the truth? Surely he as the older partner, if any, was the seducer. His cowardice perhaps was behind the clandestine nature of the affair, the concealed marriage.

The failure of his career seems to touch on other aspects of his personality and capabilities. Why did Egerton refuse to take Donne back into employment? Was it pique, annoyance, pressure of other State business? Was Donne’s sudden scandal an embarrassment to an ex-Catholic servant of the Crown in those sensitive times? Or did Egerton see no reason to rescue Donne, not wanting to be accused of nepotism on behalf of a man from just such a strong Catholic background? Was Egerton simply, tired and irritated by the whole episode, and in an unforgiving mood? Or did Egerton finally see Donne as unfit for the role, having broken confidence, betrayed trust? Why did Donne remain for the next thirteen years outside the regular social positions he coveted? He had many contacts in high places. Was his own personality too awkward, too complaining, too importunate, too abrasive? It seems that he transferred some of the blame for the situation not onto Ann, but onto the intrinsic weakness in himself that he rationalised as being derived from Original Sin. He, they, had committed an unwise action, in worldly terms. He, they, had betrayed a trust, for the sake of a deeper commitment.

He regretted his lack of a career, bitterly. It is difficult now to say whether this was all due to the one mistake, or also to his Catholic background, his own personality and temperament, his priorities as to what he saw as acceptable employment. His ambitions may have been unreasonable, the obstacles partially self-created. This is where history descends into the obscured streams of mind and motive. Events may be clear, but their origins are tangled. The words express the two men inside a single mind. On the one hand the positive love of the Songs and Sonnets, the acknowledgement of his own responsibility, the pain and grief at Ann’s death, the difficulty in forgetting her. On the other hand there is the orthodox condemnation of Woman as sinful, the scepticism regarding Woman’s capability for constancy in those same poems. There is the melancholy and plaintive way in which he writes of the difficult years. There is the darkness of his later vision, the narrow conservatism and conformity, the focus on sin and death. On the one hand a celebration of sexuality, life, mutual trust, the tender and loving tone of the verse. On the other hand the religious anguish, the complaints, the sense and fear of rejection, disgrace, failure, and continuing exclusion, which dogs the letters, the later verse, many of the sermons.

The reality was the expulsion from the Garden. If Ann is Eve, she has the silent face of Eve. We cannot hear her voice. We only glimpse her now and then, as Everywoman, as the subject of verse, or through a comment in a letter. She is continuously pregnant, or giving birth, until her death, which itself came a week after giving birth to a stillborn child. The first seventeen years of her life were childhood, love, and marriage. The last seventeen were childbearing, miscarriage, and stillbirth. She gave birth in 1603,1604, 1605, 1607, 1608, 1609, 1611, 1613, 1615, and 1616. Four of their children died young. Gaps in the sequence fall when Donne journeys abroad, in late 1605 and early 1606, in late 1611 and in 1612. On this occasion he saw a vision of his wife ‘with her hair hanging about her shoulders, and a dead child in her arms’ which was confirmed by a messenger from London. Ann had given birth to a stillborn child ‘the same day, and about the very hour’.

Was this life her choice, or her lot? Cynically one might imagine his trips abroad as a great relief! Or was she a woman who loved children, loved family life, loved him so much that it seemed right to her? After the tragic death of three children in 1613 and 1614 was she trying to replace them in her continued pregnancies? Was she a free woman making her decisions, or a martyr to the demands of her husband? Was it ignorance of birth control, or an acceptance of her destiny?

She can seem the bright shining face of the Goddess in her loving incarnations or the voiceless face of all those women in the past that a male-dominated history relegates to silence. We know she is there. She is the name in the poems, endlessly punned upon, and the embodiment of love in the poems, endlessly exalted, and worried over. She is seen through a mirror darkly, in brief flashes, in the letters. ‘I write... by the side of her, whom because I have transplanted into a wretched fortune, I must labour to disguise that from her, by all such honest devices as giving her my company and discourse; therefore I steal from her all the time which I give this letter.....But if I melt into melancholy whilst I write, I shall be taken in the manner, and I sit by one too tender towards those impressions..’ he writes from their damp, cramped house at Mitcham. In another letter, he talks about the ability to change the mind’s moods ‘I hang lead at my heels, and reduce to my thoughts my fortunes, my years, the duties of a friend, of a husband, of a father, and all the incumbencies of a family’.

In the Holy Sonnet he wrote at her death, playing, with her name, he mourned that ‘she whom I loved....my good is dead..... here the admiring her my mind did whet to seek thee God.... why should I beg more love ....’ , and again in the Hymn to Christ ‘Thou lov’st not, till from loving more, thou free my soul’. And sadly, we see her again, in the last great sermon, Death’s Duel, preached before Charles the First, in 1631, in the moment before Donne’s own death. ‘In the womb, the dead child kills the mother that conceived it, and is a murderer, nay, a parricide, even after it is dead.’

In the Songs and Sonnets, written in his youth, everything, religion also, is turned to a celebration of their Love and the Sacred Marriage. Innocence may be lost, with the Paradise Garden, but these early poems carry Paradise along with them into the wider world outside the Gates. The emblems and ideas and feelings of Catholicism, saints, relics, angels, oaths and sacraments, miracles and spirits, are brought to serve the mind searching out images of its adoration, its idolatry.‘ Souls where nothing dwells but love (all other thoughts being inmates) then shall prove this, or a love increased, there above, when bodies to their graves, souls from their graves remove.’

In Babylon, and Thebes, at Athens and Eleusis, and all over the early world, men and women celebrated the Sacred marriage of the Sun and the Earth to ensure the fertility of the universe. The marriage is echoed in alchemy, and in mystic Christianity, where Christ himself may be the Bride. In the sacred grove at Nemi a marriage like that of the King and Queen of the May, was celebrated each year between the mortal King of the Wood, and Diana, the immortal Queen of the Wood. He impersonated the oak-god Jupiter. The marriage of the priestly kings of Rome to the oak-goddess was a repetition of this rite, and Homer in the Iliad describes the union of Zeus and Hera on Mount Gargarus, the highest peak of Ida. ‘I will hide you in a golden cloud’ says Zeus ‘so that the sun himself, with his penetrating light, cannot find us through the mist’. The earth ‘threw out a bed of soft grasses beneath them, the crocus and the dew-wet lotus, and a host of hyacinth flowers, to cushion them from the ground.’ ‘Love the entangler wove their hearts together’ says Gottfried, of Iseult and Tristan ‘with a bond of sweetness, with such skill and miraculous force, that, throughout their lives that knot was never undone.’ ‘There would be given them, one death and one life, one sorrow and one joy.’

It is during these years of Donne’s marriage that Shakespeare writes the great tragedies, and the final plays, those tales of love’s disasters that end in love’s resurrection. ‘I my poor self did exchange for you, to your so infinite loss’ says Posthumous to Imogen in Cymbeline. Pericles at last recognising Thaisa, high-priestess as she now is of the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, tells the gods ‘You shall do well that on the touching of her lips I may melt and no more be seen ...’ . ‘O, she’s warm!’ cries Leontes at the ending of The Winter’s Tale, ‘ If this be magic, let it be an art lawful as eating.’ And in The Tempest, Shakespeare creates his masque in which the Goddess in triple form as Juno, Ceres and Iris, the rainbow messenger, appear. ‘Spirits, which by mine art I have from their confines call’d to enact my present fancies’ bless ‘a contract of true love’ between the lovers, Ferdinand and Miranda, entering into their ‘brave new world’. The marriage chamber is also a temple. Heirogamy, the marriage of the god and goddess, is the heart of the myth. Society makes the laws of the world, but the human heart makes the laws of love. Sacredness also sits within the circle of the marriage crown.

Is not Love a deity? Love is not merely appetite. ‘Why love among the virtues is not known, is that love is them all, contract in one.’ For the virtuous man, Love must encompass every good. And the incarnation of love, that which allows the sacred marriage, is Woman. The soul, with its frailties, is female, and Women are angels. ‘As is ‘twixt air and angel’s purity, ‘twixt women’s love, and men’s will ever be.’ ‘Yet I thought thee, (For thou lov’st truth) an angel, at first sight.’ Woman is the divine essence brought below, embodied, as Shakespeare embodies her in those arcane personifications of the Pearl, in his heroines of the last plays. ‘Or if when thou, the world’s soul, go’st, it stay, ‘tis but thy carcase then’ Donne attests. She is his ‘dearest heart, and dearer image’ on whose name he plays, waking from his dream ‘to love more’. And dream is the halfway house between the substantial world and the world of spirit, between earth and heaven. ‘If ever any beauty I did see, which I desired, and got, ‘twas but a dream of thee.’

If Woman is the world’s soul, an angel in a dream, and Love is all virtue, marriage is a temple, and a divine union, or an image of one. The universe is made and is renewed in the infinite contracted space where lovers are. ‘This our marriage bed, and marriage temple is’. ‘So we shall be one, and one another’s all.’ They ‘one another keep alive’ and ‘lover’s hours be full eternity’. They ‘sigh one another’s breath’ and when they wept tears they wept floods ‘and so drowned the whole world, us two; oft did we grow to be two chaoses’. As the lovers re-create in their bubble of space and time the hierogamy of the gods in the infinite and eternal, so all change to their world changes the universe also. They indeed become one another’s body as well as spirit ‘so to integraft our hands, as yet was all the means to make us one, and pictures in our eyes to get was all our propagation.’ This holy marriage is, as Donne celebrates in an epithalamion, ‘joy’s bonfire, then, where love’s strong arts make, of so noble individual parts, one fire of four inflaming eyes, and of two loving hearts.’ And remembering Augustine, and the imagery of the alchemical mystic wedding ‘Here lies a she sun, and a he moon here, she gives the best light to this sphere, or each is both, and all, and so they unto one another nothing owe.’

‘And though they make Apollo a wizard and a physician’ writes Augustine in the City of God ‘to make him a part of the world they say he is the sun, and Diana, his sister, is the moon.... And Ceres, the great mother, her they make the earth and Juno besides. Thus the secondary causes of things are in her power, though Jove is called the full parent, as they affirm him........and so, by all these specific gods they intend the world: sometimes totally and sometimes partially: totally as Jove is: partially as ... Sol and Luna, or rather Apollo and Diana. Sometimes one god stands for many things, and sometimes one thing presents many gods.’

This marriage, completely achieved, goes beyond sexuality into that realm where sex is irrelevant, the lovers ‘forget the He and She’, since ‘to one neutral thing both sexes fit. We die and rise the same, and prove mysterious by this love’. In the Ecstasy, Donne’s deepest poem on the theme ‘This ecstasy doth unperplex (We said) and tell us what we love, we see by this it was not sex, we see, we saw not what did move’. And yet love is only possible for the lovers in the flesh. ‘We are the intelligences, they the spheres’ and there is no reality in space and time but through the physical body. ‘The soul with body, is a heaven combined with earth’. ‘This soul limbs, these limbs a soul attend, and now they joined’. In Air and Angels, Donne is explicit. ‘But since my soul, whose child love is, takes limbs of flesh, and else could nothing do, more subtle than the parent is, Love must not be, but take a body too..’. Elsewhere ‘though mind be the heaven, where love doth sit, beauty a convenient type may be to figure it.’ and finally in the Ecstasy ‘So must pure lovers’ souls descend t’affections, and to faculties, which sense may reach and apprehend, else a great prince in prison lies. To our bodies turn we then, that so weak men on love revealed may look; Love’s mysteries in souls do grow, but yet the body is his book.’

Donne is not making a system. He is playing in a sense among inherited metaphors, but the effect is clear. The divine, incarnate in Woman, descends to the sphere of the actual. In a mystical marriage, encompassing sexuality and spirituality, Love which is all the virtues, may, in the bounded and limited space and time of the lovers, reach out to contain the whole Universe and Eternity, in a complete and inward union, hidden from the outside world. It is both sacrilegious, and a celebration of the most sacred. It is a turning inward into the private, hidden, and secret universe of the individual mind, and still an ultimate reaching out to the other. It can appear socially subversive. It nevertheless represents a refuge for the Goddess, for the abused and persecuted image of ancient holiness, in a place beyond place, and a time beyond time. It is also the Protestant solution as long as it is kept within orthodoxy, within marriage. Yet it represents a fatal dichotomy. Sexuality and sacredness withdraw from the outer world to be celebrated only within the inner world.

The transubstantiation of spirit into flesh mirrors the conversion of the bread and the wine, which became a crux of the argument between the Elizabethan Churches. As Shakespeare in the drama, so Donne in his Songs and Sonnets attempted to save the Goddess, the image of tender love, and hold out a testimony and a warning. That he seems partially to renege on this, in his later life, does not detract from the achievement, which carries across to modernity, while his Anglican faith seems now the superseded voice of the past.

‘And since the lovers realised’ says Gottfried, ‘that there was between them just one mind, one heart, and one will, the pain began at the same time to die and to come to life....He kissed her and she kissed him, lovingly, tenderly: and that, for Love’s cure, was a joyful start.’ Love is the lovers’ response to power, to the established forces of a society that dehumanises the individual and seeks to destroy and seduce his or her integrity. The single one, or the union of two, is the true and authentic life, in that island of the human, where society is included as mind, but excluded as power. The genuine has to overcome, continually, the conventional and the authorised, in order to defeat the wasteland.

Donne, despite contacts with influential patrons, only achieved a solid social position, when in 1615 he was ordained, and entered the Anglican Church. He had, he says, defending his earlier apostasy, ‘for a long time, wrestled with the examples and reasons of Catholicism. I apprehended well enough that this irresolution not only retarded my fortune, but also bred some scandal.’ His hands on a secure and respectable living, he becomes socially authoritarian, and reactionary. Achieving an orthodox career at last, he seems to become more orthodox than the orthodox, compensating for past rejections in his new conformism. A sympathetic view is that he had come in from the cold, later than he should have done, repairing his betrayal of trust by a commitment to the coming world of Protestant dominance. A sympathetic view takes into account the agonies of Catholic persecution and the irrelevance of dogma to a genuine loving Christianity. The unsympathetic view sees yet another betrayal, of his background and true faith, of the territory of individual love, which he had marked out, as a tender refuge, and an unfallen paradise. The subverter has been subverted. He has sold out his principles.

Motives are inscrutable, often unconscious. In the end judgement is of no consequence to those who think he had reached, at least for one period of his life, the modern truth of personal life, in a way which helps delineate the battleground of our future. The future is where the species will be forced to consider the life that is human, and the life in a Nature under threat. The future is where mind and body will become transmutable, separated, engineered and replicated, where we have to confront our own transformation of the planet and of ourselves. What might we be, beyond the natural, human processes recreated and amplified in conscious circuitry? Those beings, that circuitry, a separate or a related mind-laden species, no longer wholly organic - our lifespan, our parenthood, our sexuality, our sensations, our environment, and our aspirations mutated radically and forever?

Donne is a reference point for the sphere of inward, humane values, which we must understand in order to influence the future. Those values are real. They are in us from our own genetic inheritance, and from what our cultures have built upon them. They are ours by Nature and by Nurture. They include love, compassion, honesty and courage.

Donne’s own complex self, that changeable inner universe, the ‘infinite hive of honey, this insatiable whirlpool of the covetous mind, no anatomy, no dissection hath discovered to us’ suffered its own self-inflicted agonies, there is no doubt. He said, even while his wife was alive, that he had ‘much quenched my senses, and disused my body from pleasure, and so tried how I can endure to be mine own grave.’ His belief in his own sinfulness became stronger, feeling he had been ‘a temple of the spirit divine’, ‘till I betrayed myself’. He quotes Augustine, confessing all sins to be his sins. ‘The sin that I have done, the sin that I would have done, is my sin....’. He makes a final plea, or is it a final sad betrayal of what he once was and of the woman he loved. He tells his Christ (who ‘with clouds of anger do disguise thy face; yet through that mask I know those eyes’) that ‘Thou lov’st not, till from loving more, thou free my soul.’ Here was a man who feared rejection all his life, and now in his heart sought to avoid it, even by asking that his love of her be expunged.

‘Whisper in my heart’ says Augustine to his God; ‘you who are my only Refuge, all that is left me in this world of men.’ Donne’s fears are real to him. ‘My ever-waking part shall see that face, whose fear already shakes my every joint’, his ‘horror beyond our expression, beyond our imagination’ to ‘fall out of the hands of the living God.’ ‘I have a sin of fear’ he writes ‘ that when I have spun my last thread, I shall perish on the shore’.

He has the sensitivity to time, which is Existential. ‘What if this present were the world’s last night?’ ‘What a minute is man’s life’. ‘Do you not know’ writes Kierkegaard, ‘that there comes a midnight hour when every one has to throw off his mask?’ ‘God never says you should have come yesterday’ says Donne ‘he never says you must again tomorrow, but today if you will hear his voice, today he will hear you.’ ‘Your today’ says Augustine ‘is eternity’. ‘The minute that is left, is that eternity’ says Donne ‘which we speak of; upon this minute dependeth that eternity: And this minute, God is in this congregation, and puts his ear to every one of your hearts.’

Death also is one of his themes, not that dying of the body in the ‘little death’ of sexual union, but that ‘desire of the next life’, which he wrote of in one of his letters. It is coupled with the theme of the dissolution of the body in physical death ‘that excremental jelly’. ‘Who knows the revolutions of the dust?’ in the graveyard, of ‘they whom we tread upon’, ‘a dissolution of dust’. Death ‘comes equally to all, and makes us all equal when it comes.’ That was a truth already causing others in his society to question the many inequalities that existed before death.

He puts his faith in that resurrection which his religion promised, in the otherworld. ‘It is in his higher power to give us an issue and a deliverance, even then when we are brought to the jaws and teeth of death, and to the lips of the whirlpool, the grave.’

Yet it is sometimes in strange terms that he envisages that next world. He assaults heaven in order to assume an otherworldly mantle. Or seeks to be assaulted. ‘Batter my heart, three-personed God; for you as yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend.....Divorce me, untie, or break that knot again, take me to you, imprison me, for I except you enthral me, never shall be free, nor ever chaste, except you ravish me’. Yet he declares ‘I launch at paradise’. ‘As soon as my soul enters into heaven I shall be able to say to the angels, I am of the same stuff as you, spirit and spirit, and therefore let me stand with you’. ‘Those beams of glory which shall issue from my God, and fall upon me, shall make me ... an angel of light ... I shall be like God ... I shall be so like God as that the Devil himself shall not know me from God.’ Whether or not this is good theology it is all of a piece with that fear of rejection, that longing for identity, that desire for union and a sensual closeness, which erupt out of Donne’s inner being all his life through.

Ann died in 1617. It was after her death that Donne was elected as Dean of St Paul’s preaching his great sermons, in front of James the First, and after James’s death in front of Charles. In 1623 his daughter Constance married Edward Alleyn, the great actor who had played the lead in Marlowe’s tragedies. In 1627 his daughter Lucy died, and in the January of 1631 his mother. On the 25th of February that year, ill himself, he preached his last sermon, Death’s Duel, before Charles, based on Psalm 68, a meditation on death. There is an irony. For Donne was a part, as Essex, and Raleigh, and Marlowe were a part, of that movement towards a Protestant, Parliamentary, commercial and ultimately secular England, which had no meaningful place for the myth of the Divine Right of Kings. There was no place for hereditary privilege, for arbitrary royal power, which itself derived obliquely from the ancient worship of the Goddess, and the reign of her divine consort. This King to whom he preached was to feel the full weight of that change.

Though later, England, for reasons of political stability, reinstated the monarchy, and watched the revolutionary principles go abroad to France and America, carried by Tom Paine and others, the monarchy, in the sense of a nexus of power, mythologically conceived and unquestionable in its authority, was over. The Divine Right of Kings, which Elizabeth tried to uphold, was gone. The modern world, the secular state, democracy, science, commerce, industry, emerged from the chrysalis.

The Elizabethans may not have understood that process, or consciously wished it to happen. They may even have perceived themselves to be doing the opposite; Essex seeking to modify the power of the Queen but not destroy it; Raleigh writing his History of the World to demonstrate the workings of Providence; Donne preaching orthodoxy and salvation in the next world, not in this. Only Marlowe may have half-realised what was in train in the depths of his own society, though he too is focused on the structures of the old world-order. It is in their lives, the effect of their lives, and what other men and women thought as a result of their actions and writings, that they influenced the future.

Essex and Raleigh weakened kingship, through popular reaction to the injustice and arbitrariness of their executions, and the process they assisted, transference of the divine myth to a mortal woman. With converts like Donne they weakened the remnants of Catholicism and paved the way for the Protestant world. Sitting in Parliament they strengthened its role. Raleigh in particular, unwittingly, gave a model for balanced participative government. Marlowe is a type of the ambitious extremist writer who is the life-blood of revolution. Donne’s Songs and Sonnets authorise that individual view of life, that subverts hereditary power in favour of what Kierkegaard called ‘the most inward and sacred thing of all in a man, the unifying power of personality’.

All of them, by being Individuals, in the fullest sense, opened the way for other individuals, for the testing of experience against one’s own inner and outer experience, for the right to apply reason and analysis, intellect and judgement, to received wisdom and to the world beyond. Raleigh is the geographical explorer, but Marlowe and Donne explore internally, casting and recasting thought and situation to clarify and celebrate.

Sitting in the congregation to which Donne preached were many who eleven years later would see England enter a Civil War, precipitated by the King’s policies. Donne was preaching to the last English monarch for whom Divine Right seemed a reality. Economic mismanagement, unjust taxation, individualism and ambition, the growth of secular and democratic power in Parliament, above all the suppressed Puritan extreme reacting against Catholicism and eager to establish its presence, as it had already in America, were all factors in Charles’ miserable fate. Deeper than that, was the reality that the myth had died, that Divine Kingship was finished.

And Kingship diminished to the actions of an arbitrary mortal, is merely the rule of power. If power is lost, then the role of royalty is lost, and where it is perpetuated it becomes a pitiful comedy, at the last a farce. The ideas set in train in Elizabethan England, the complex undercurrents; of justice, expanding horizons, secular authority, democratic government, individual conscience, and commercial ambition even though not ascribed to by the actors, often are carried forward by their actions. As Donne preached to Charles the First on Death, he strangely embodied, and had sealed with his own apostasy, the Protestantism that was the precursor of the Puritan Revolution. Just as in his earlier secularisation of the myth in the poetry of Love he embodied the Individualism that was to deal ritual death to the king, in a symbolic ending of sacred kingship, the myth putting paid to the myth for all time, in England.

Before he died, Donne left his sickbed to stand naked under his shroud on a large wooden urn, so that eyes closed, a life-size sketch could be made. Nicholas Stone later carved the statue which, miraculously surviving the Great Fire, still stands in Wren’s new St. Paul’s. Donne’s illness was fatal. He died on the 31st March 1631.

His astrological chart for the day of his death shows Saturn returned for the second time to its natal place in Scorpio, and Pluto the planet of fate in detriment in the opposing sign of Taurus. Moon, Mars and Mercury, which are emotion, life-energy and mind, were all conjunct his natal Pluto in Pisces, the Sign of religion, and all in opposition to Uranus the planet of this final, fatal change, while linked in trine to Saturn, which in turn was sextile Uranus. The sun was square his natal Uranus, also signalling fundamental change.

Astrology’s chance pattern, its random configuration is apt and fit for the man. Saturn returns to mark the completion of the second half of his life, marriage to death, making two halves of approximately twenty-nine and a half years, that period of an average circuit of Saturn around the Sun. That second half was punctuated in turn halfway by Ann’s death. At the end fate looks across at cold, constricting Saturn, from earthy Taurus, and life, mind, heart and sexuality are challenged finally by the planet of change Uranus. Neptune, ruler of poetry is silent. Pisces the sign of religion and of tears, Scorpio the sign of depth and sexuality, have their last say.

Donne had exalted secular love and made it sacred. Coming from a Catholic background, living through the dangerous 1590’s and into the Stuart age, he brought a new autobiographical sincerity, a new individualistic voice into poetry. If he made mistakes he knew himself to be fallible. If he altered from his early Catholicism, if he denied his own early triumph of love, if he fought the cramping and dark battle to wean his loving feelings to an abstract deity, if he feared rejection, and sought in the end the comfort of acceptance, if ultimately he did violence to the truths of his own heart, then those were his decisions.

He is, like Marlowe, Essex and Raleigh, a great Individual, in an age of individual courage, moral intensity, and freedom of thought. England recapitulated in a sense the Greek experience, which had lain dormant for two thousand years until the Renaissance. The Greeks also had exchanged the gods for pure reason, Athene’s legacy. They also replaced myth by Socratic questioning. They too had reached, though they could not sustain, in Athens, the conditions for the modern world, for the emergence of science and technology, democracy, and rational justice, upheld by the laws, embodied in the citizen. They too killed the Goddess, and the Gods, as Euripides knew.

If we look at both experiences, it informs our own situation. How to counter the rapaciousness of physical power and the assault of pure reason which potentially lay waste both Nature and Human Nature? How to save a vision of sacred humanity within an intrinsically and irreversibly secular world? How to balance the sceptical, enquiring, pragmatic and desacralising mind, with the mind of unconditional Love?

‘Man is a world’ said Donne. Within that world, within the mind, he exhorted ‘Be thine own palace or the world’s thy gaol.’ He had seen Essex, the great courtier, confined, imprisoned, incapable of turning his thoughts ambitions and aspirations into coherent action. Donne was sensitive, who more so, to the dangers of isolation, separation, division, the possibilities of rejection, and self-destruction. His truest vision is of unity, a sacred unity, of man and the world, of body and spirit. ‘So must pure lovers’ souls descend t’affections, and to faculties, which sense may reach and apprehend, else a great prince in prison lies.’